A detailed foundation of quaternion mathematics.

This is part of a series. The other articles are:

Table of Contents

- Extending the complex numbers

- Quaternion foundations

- Properties of quaternions

- Rotations with quaternions

- Conclusion

Quaternions

Extending the complex numbers

In 1843, Sir William Rowan Hamilton was seeking to extend the complex numbers to 3 dimensions. Complex numbers had been introduced in 1572 and it had taken a while for them to gain popular acceptance. René Descartes coined them imaginary numbers in 1637. Leonhard Euler and his peers had greatly improved our understanding of them in the 1700s. Carl Freidrich Gauss - a famous contemporary mathematician of Hamilton - had proved more theorems involving complex numbers in the early 1800s. By 1843, it was time to extend them.

Hamilton had already tried to do this for 10 years. The obvious idea was to try a number of the form:

\[z = a + bi+ cj \;,\; i^2=j^2=-1\]This however leads to an inconsistent algebra. Without going deep into the theory, a mathematical algebra needs to be consistent so that we can use logic to unambiguously derive more conclusions. For example, in real number algebra there is only one number that can satisfy $xx^{-1}=1$ for a given $x$ because every number has a unique inverse. If $x=6$, then $x^{-1}$ can only be $\tfrac{1}{6}$.1

Proof of inconsistency

This is a proof by contradiction. There must be real numbers $a$, $b$ and $c$ that satisfy $$ ij = a + bi + cj \; ; \; a,b,c \in \mathbb{R}$$ But if we multiply by $i$: $$ \begin{align} \times i: \; -j &= ai - b + cij \\ &= ai - b + c(a + bi + cj) \\ \therefore 0 &= (ac - b) + i (a + bc) + j (c^2+1) \end{align} $$ This requires that all coefficients equal zero, but then $c^2=-1$ and thus $c$ must also be imaginary. This is a contradiction because $c$ must be real.

Another problem is that multiplication must preserve length. With complex numbers, we take it for granted that:

\[\| z_1 \| ^2 \| z_2 \| ^2 = \| z_1 z_2 \| ^2\]This is because multiplying two complex numbers results in a third complex number:

\[(a_1 + b_1i)(a_2 + b_2i) = (a_1a_2 - b_1b_2) + (a_1b_2+b_1a_2)i\]For the 3D complex number this is not always possible. This can be proved for complex numbers with only integers through Legendre’s three-square theorem which states that integers of the form $n=4^a(8b+7)$ cannot be represented as the sum of three squares of integers. For example:

\[(0^2 + 1^2 + 2^2)(2^2 + 2^2 + 2^2)=60=4(8 + 7)\]Hence we have a number that is a product of two sums of three squares, but it cannot be written as a sum of three squares, and so cannot be the magnitude of a 3D complex number.2

If we multiply two of these 3D complex numbers out, we get terms in $ij$ that have no meaning:

\[\begin{align} (a_1 + b_1i + c_1j)(a_2 + b_2i + c_2j) =& (a_1a_2 - b_1b_2 -c_1c_2) + \\ & (a_1b_2+b_1a_2)i + (a_1c_2+c_1a_2)j + \\ & b_1c_2ij + b_2c_1ji \end{align}\]The final problem is that rotations in 3D are ordered. Therefore the mathematics describing them must be ordered. This is the same as saying it must be non-commutative: $ab\neq ba$.

Quaternion foundations

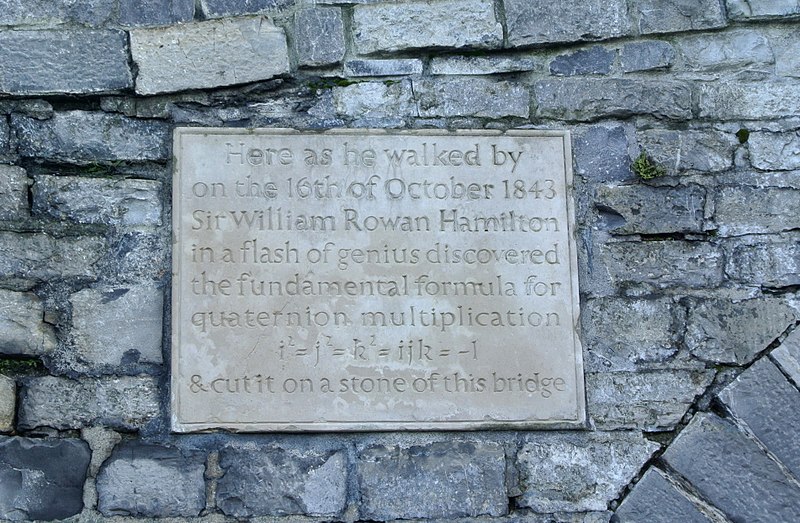

Owing to the above problems, Sir William Rowan Hamilton had difficulties multiplying triples, as he called them. But on 16 October 1843, as he was walking past a canal in Dublin, Hamilton had the great insight that he needed a fourth dimension to describe 3D rotations. Three independent axes and a fourth to describe the size of the scaling. Overcome with euphoria, Hamilton carved the fundamental equation $ijk=-1$ into the Broom bridge (also called Brougham Bridge). The engraving faded but a plaque has been put in its place.

For a version of this in Hamilton’s own words, see this letter to he wrote to John T. Graves the following day: www.maths.tcd.ie/pub/HistMath/People/Hamilton/QLetter/QLetter.pdf.

Here is a definition of these quaternions:

Definition: Quaternion

/kwəˈtəːnɪən/

A quaternion is a number of the form $$s + xi+yj + zk \; ; \; s, x, y, z \in \mathbb{R}$$ where the basis elements $i$, $j$ and $k$ obey the following rules of multiplication: $$i^2 = j^2 = k^2 = ijk = -1 \;,\; ij=k \;,\; ji=-k$$

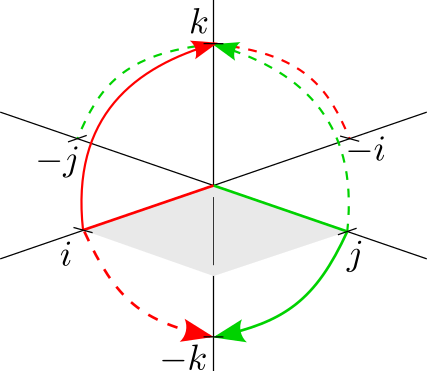

Like with the imaginary number $i$, each of the basis units corresponds to a 90° rotation about an axis. Consider $ij=k$. This has two interpretations:

- The point $i$ post-multiplied by $j$, resulting in a clockwise rotation about the $j$ axis to the point $k$ (red solid line).

- The point $j$ pre-multiplied by $i$, resulting in an anti-clockwise rotation about the $i$ axis to the point $k$ (green dashed line).

Similarly for $ji=-k$:

- The point $j$ post-multiplied by $i$, resulting in a clockwise rotation about the $i$ axis to the point $-k$ (green solid line).

- The point $i$ pre-multiplied by $j$, resulting in an anti-clockwise rotation about the $j$ axis to the point $-k$ (red dashed line).

In general, pre-multiplication results in anti-clockwise rotations and post-multiplication in clockwise rotations.

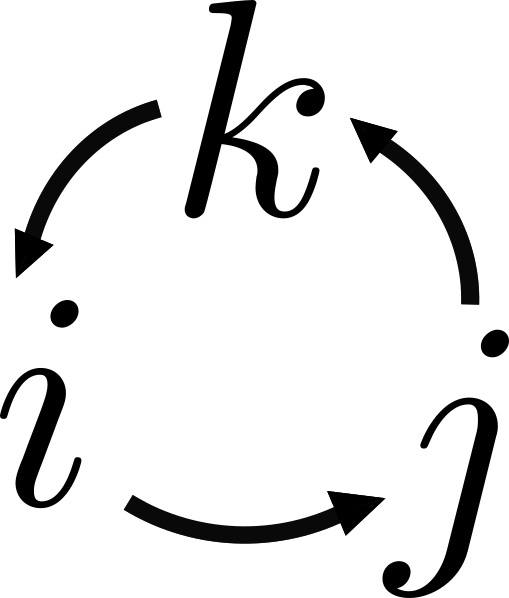

I like to use the following mnemonic to remember the rules:

Going anti-clockwise with the arrows results in positive products, such as $ jk = i$, but going clockwise against the arrows results in negative products, like $kj = -i$.

Unlike complex numbers, $i^2=j^2=k^2=-1$ has no direct interpretation because these numbers lie in the fourth dimension.3

Properties of quaternions

Addition and subtraction

Addition and subtraction are done using normal algebra rules:

\[\begin{align} q_1 + q_2 &= (s_1 + x_1i+y_1j + z_1k) + (s_2 + x_2i+y_2j + z_2k) \\ &= (s_1 + s_2) + (x_1 + x_2)i + (y_1 + y_2)j + (z_1 + z_2) k \\ q_1 - q_2 &= (s_1 + x_1i+y_1j + z_1k) - (s_2 + x_2i+y_2j + z_2k) \\ &= (s_1 - s_2) + (x_1 - x_2)i + (y_1 - y_2)j + (z_1 - z_2) k \end{align}\]Multiplication

Quaternions obey the distributive law, so multiplication by a scaler can be applied to each element individually. In this case, the multiplication is commutative:

\[\begin{align} q r &= rq = rs + rxi + ryj + rzk \end{align}\]Multiplication by a quaternion is also done with the distributive law:

\[\begin{align} q_1 q_2 =& (s_1 + x_1i+y_1j + z_1k) (s_2 + x_2i+y_2j + z_2k) \\ =& s_1 (s_2 + x_2i+y_2j + z_2k) + x_1i (s_2 + x_2i+y_2j + z_2k) + \\ & y_1j (s_2 + x_2i+y_2j + z_2k) + z_1k (s_2 + x_2i+y_2j + z_2k) \\ =& s_1s_2 + s_1x_2i+s_1y_2j + s_1z_2k + x_1s_2i - x_1x_2 + x_1y_2 k - x_1z_2j + \\ & y_1s_2j - y_1x_2k - y_1y_2 + y_1z_2 i + z_1s_2k + z_1x_2j - z_1y_2i - z_1z_2 \\ =& (s_1s_2 - x_1x_2 - y_1y_2 - z_1z_2 ) + \\ & (s_1x_2 + x_1s_2 + y_1x_z - z_1y_2 )i + \\ & (s_1y_2 - x_1z_2 + y_1s_2 + z_1x_2 )j + \\ & (s_1z_2 + x_1y_2 - y_1x_2 + z_1s_2 )k \end{align}\]In general, $q_1q_2 \neq q_2 q_1$. This is only true if $q_1=q_2$ or if either quaternion is a scalar.

When writing code for quaternions it is easiest to hard code this 16 term expression as the result of a multiplication of two quaternions rather than writing the rules for $i$, $j$, $k$. This was done in the code for the quaternion in part 1.

Quaternion multiplication does indeed preserve length:

\[\| q_1 \|^2 \| q_2 \|^2 = \| q_1 q_2 \| ^2\]Where the magnitude of a quaternion is:

\[\| q \|^2 = s^2 + x^2 + y^2 + z^2\]When Hamilton verified this property, he knew his theory of quaternions was correct. It turns out though that he had only rediscovered Euler’s four-square identity, which Euler had proved almost 100 years prior.

Inner product

The inner product is another type of multiplication that is useful. It is defined as the sum of the product of corresponding co-ordinates:

\[q_1 \cdot q_2 = s_1s_2 + x_1x_2 + y_1y_2 + z_1z_2\]The inner product of a quaternion with itself is its magnitude:

\[q \cdot q = \| q \| ^2 = s^2 + x^2 + y^2 + z^2\]In 2 or 3 dimensions the inner product can be directly related to the angle $\Omega$ between two vectors. We can simply extend this formula to quaternions even though we cannot visualise an angle between 4D vectors:

\[q_1 \cdot q_2 = \| q_1 \| \| q_2 \| \cos\Omega\]In part 4 this will be used to make a smooth function for interpolation.

Conjugation

For convenience, the conjugate $q^{*}$ of a quaternion is defined as:

\[q^{*} = (s + xi + yj + zk)^{*} = s - xi - yj - zk\]The conjugate can be used to calculate the magnitude of a quaternion:

\[q q^{*} = \| q \| ^2 = s^2 + x^2 + y^2 + z^2\]Inverse and division

The inverse of a quaternion $q^{-1}$ is the unique quaternion that satisfies $qq^{-1} = 1 + 0i + 0j +0k $. This quaternion is given by:

\[q^{-1} = \frac{q^{*}}{\| q \| ^2 }\]Proof:

\[qq^{-1} = q\frac{q^{*}}{\| q \| ^2 } = \frac{\| q \| ^2}{\| q \| ^2} = 1\]Division is equivalent to multiplication by the inverse of a quaternion:

\[q_1/q_2 = q_1q_2^{-1}\]Unit quaternions

A quaternion with magnitude 1 is called a unit quaternion. Unit quaternions lie on a hypersphere of 4 dimensions, which is not possible to visualise. However we can get a feel of it through values:

| $ |q| < 1 $ | $|q| = 1 $ | $ |q| > 1 $ |

|---|---|---|

| $ 0 $ | $ 1 $ | $10 $ |

| $0.8i $ | $1i $ | $ 1i + 2j + 3k $ |

| $ 0.1 + 0.1i + 0.1j + 0.1k $ | $0.5 + 0.5i + 0.5j + 0.5k $ | $0.9 + 0.9i + 0.9j +0.9k$ |

| $ 0.1 + 0.2i + 0.3j + 0.4k$ | $0.4 + 0.5i + 0.6j+\sqrt{0.23}k$ | $0.5 + 0.6i + 0.7j +0.8k$ |

For a unit quaternion, the inverse is $q^{-1} = q^{*}$.

Using a normal vector $\hat{n}=n_xi + n_yj + n_zk$ with magnitude $ | \hat{n} | = 1$, the following unit quaternion can always be constructed:

\[q = \cos(\theta) + \hat{n} \sin(\theta)\]Exponential, logarithm, and power functions

We can define an exponential-like function for unit quaternions similar to the complex number exponential, which will have similar properties:

\[e^{\hat{n}\theta} = \cos(\theta) + \hat{n} \sin(\theta)\]With an inverse logarithm-like function:

\[\log(q) = \log(\cos(\theta) + \hat{n} \sin(\theta)) = \log(e^{\hat{n}\theta}) = \hat{n}\theta\]The general exponentiation formula is defined based on these:

\[q^t = e^{t \log q}\]We can then find a similar formula to de Moivre’s formula:

\[q^t = (e^{t (\hat{n}\theta)}) = (e^{\hat{n}(t\theta)}) = \cos(\theta t) + \hat{n} \sin(\theta t) \; , \; \| q \| = 1\]Please see this Wikipedia article for formulas with non-unit quaternions. Please see Quaternions, Interpolation and Animation by Dam, Koch and Lillholm for more formal proofs of powers with quaternions.

Rotations with quaternions

Finally, we have enough knowledge of quaternions to calculate rotations.

Multiplying a 3D vector by a 4D quaternion will result in a rotation and scaling in 4 dimensions. To avoid scaling, we use only unit quaternions. To avoid a 4th dimension, we pre-multiply by the quaternion and post-multiply by its conjugate:

\[v_r = qvq^{*}\]This type of operation which uses an operator and then its inverse is called a commutator.

This formula works because

- Pre-multiplying rotates a vector anti-clockwise and post-multiplying rotates it clockwise.

- Rotating about a negative axis reverses the direction of rotation.

When we combine these effects, post-multiplying with a negative axes (because of the conjugate) rotates the vector anti-clockwise, but the 4th dimension part is still rotated clockwise and hence cancels out with the pre-multiplication.

Here is a more formal proof. This is a nice proof because working through it gives further insight into the problem:

Proof of rotation formula

Consider a vector $v=xi+yj+zk$ rotated by a quaternion $q = \cos\theta + \hat{n}\sin\theta$. The co-ordinate axes is arbitrary, so define a new axis in line with the normal axis $\hat{n}$ so that $k' = \hat{n}$. Then $v$ can be represented in these new co-ordinates as $v=x'i'+y'j'+z'k'$.

More detail: transformation of co-ordinates ⇩

Because the vector is rotated by twice the angle, $q$ is usually chosen to rotate half an angle, so that $qvq^{*}$ rotates one angle:

\[q= \cos(\tfrac{\theta}{2}) + \hat{n}\sin(\tfrac{\theta}{2})\]Conclusion

Congratulations for reaching this far. I hope you now know the basics of quaternions. There is enough detail here to write a fully functioning quaternion implementation. Most of these functions can be found in the code for the graph in part 1. The next and last section focuses on using interpolations for animations with quaternions.

For the curious minded, the algebraic group that includes the real numbers, complex numbers and quaternions has many more relatives.4 They are made with the Cayley-Dickson construction. The next algebra in the group are the octonions. These have eight basis units, made of one real part and seven imaginary parts. They are non-cummutative ($ab \neq ba $) and non-associative ($(ab)c \neq a(bc)$). For more detail, a good starting point is the Wikipedia page: Octonions. It is an open question whether any of these higher order algebras like octonions have a physical connection with reality.

-

Some ambiguities do exist through multi-valued functions. For example if $x^2=1$ , then $x$ can be $1$ or $-1$. But these ambiguities can be dealt with if the underlying algebra is consistent. ↩

-

A solution can be constructed if we allow non-integers, for example $4^2 + 6^2 + \sqrt{8}^2 = 60$. However then the solution is not closed under addition and multiplication (because we have use a square root), which hinders efforts to make a consistent algebra. ↩

-

An irony of quaternions is that the real part is in the 4th dimension and is therefore more “imaginary” than the three imaginary parts $i$, $j$ and $k$. ↩

-

Correction: an earlier version of this post claimed that this family only consists of four algebras: the reals, the complex numbers, the quaternions and the octonions. However this discussion on HackerNews pointed out that was wrong, as the Cayley–Dickson construction can be applied arbitrarily many times. ↩