A random forest classifier in 270 lines of Python code. It is written from (almost) scratch. It is modelled on Scikit-Learn’s RandomForestClassifier.

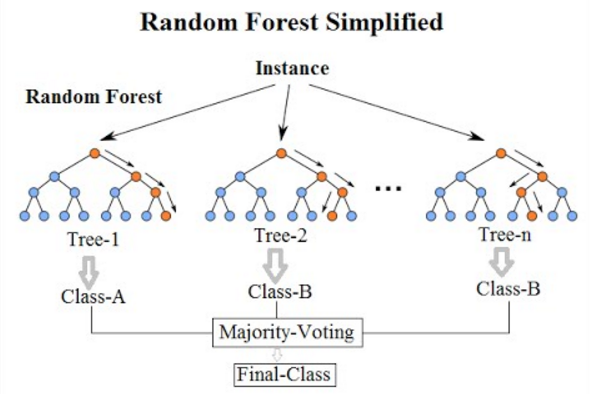

I recently learnt about Random Forest Classifiers/Regressors. It is a supervised machine learning technique that performs well on interpolation problems. It was formally introduced in 2001 by Leo Breiman. They are much easier to train and much smaller than the more modern, but more powerful, neural networks. They are often included in major machine learning software and libraries, including R and Scikit-learn.

There are many article describing the theory behind random forests. See for example 1 or 2. By far the best and most detailed explanation I have seen is given by Jeremy Howard in his FastAI course. A few sources describe how to implement them from scratch, such as 3 or 4.

My aim here is to describe my own implementation of a random forest from scratch for teaching purposes. It is assumed the reader is already familiar with the theory. I hope this post will clarify in-depth questions. The first version was based on the code in the FastAI course, but I have made it more advanced. The full code can be accessed at my Github repository. The version presented here is slightly simpler and more compact.

Scikit-learn’s RandomForestClassifier is far superior to mine. It is written in several thousand lines of code; mine was written in just 270. The main advantages of it are:

- it is much faster (by more than 100x) because it is written in Cython, utilises multiple cores to parallelise jobs and also because of more advanced coding optimisation algorithms.

- it has more options and features for the user.

- it does more data validation and input checking.

Having been inspired by Jeremy Howard’s teaching methods, I will present this post in a top-down fashion.

First I’ll introduce two datasets and show how the random forest classifier can be used on them.

Next, I’ll explain the top level RandomForestClassifier class, then the DecisionTree class it is composed of,

and finally the BinaryTree class that that is composed of.

All code is also explained top-down.

Practice Data Sets

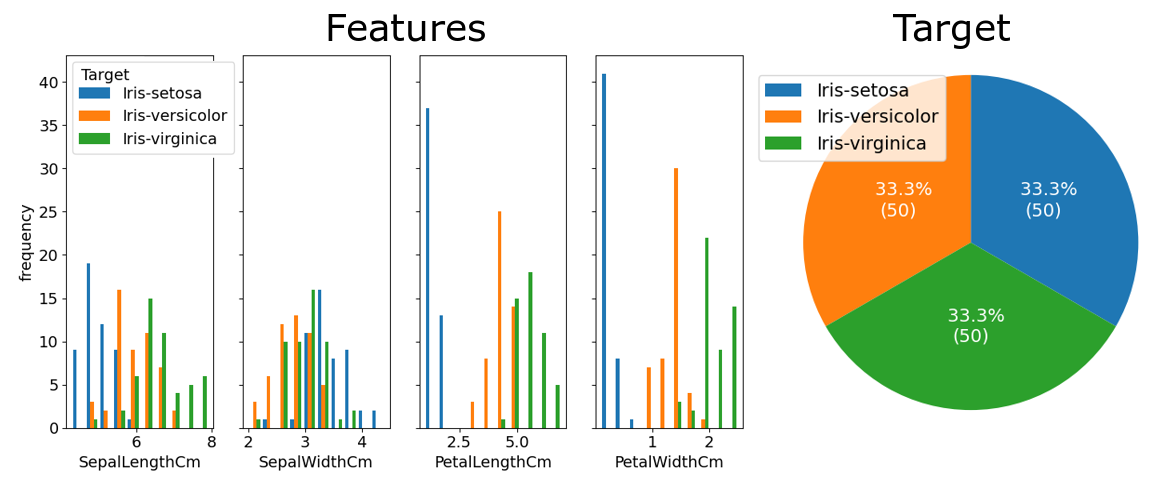

The Iris flower dataset

The Iris flower dataset is commonly used for beginner machine learning problems. The full dataset can be found on Kaggle at www.kaggle.com/arshid/iris-flower-dataset. It consists of 150 entries for 3 types of iris plants, and 4 features: sepal length and width, and petal length and width.1

The variable distributions are as follows:

Based on these, a simple baseline model can be developed:

- If PetalLength < 2.5cm, class is Setosa.

- Else determine scores score1 and score2 as follows:

- score1: add 1 for each of the following that is true:

- 2.5cm < PetalLength ≤ 5.0cm

- 1.0cm≤ PetalWidth ≤ 1.8cm

- score2: add 1 for each of the following that is true:

- 7.0cm≤ SepalLength

- 3.5cm≤ SepalWidth

- 5.0cm≤ PetalLength

- 1.7cm< PetalWidth

- score1: add 1 for each of the following that is true:

- If score1 > score2, classify as Veriscolor. If score1 < score2, classify as Virginica. If score1 = score2, leave unknown, or classify at random.

This simple strategy guarantees that 140 samples, which is 93.3% of the samples, will be correctly classified.

I used my code to make a random forest classifier with the following parameters:

forest = RandomForestClassifier(n_trees=10, bootstrap=True, max_features=2, min_samples_leaf=3)

I randomly split the data into 120 training samples and 30 test samples. The forest took 0.23 seconds to train. It had trees with depths in the range of 3 to 7, and 65 leaves in total. It misclassified one sample in the training and test set each, for an accuracy of 99.2% and 96.7% respectively. This is a clear improvement on the baseline.

This is a simple flattened representation of one of the trees. Each successive dash represents a level lower in the tree, and left children come before right:

000 n_samples: 120; value: [43, 39, 38]; impurity: 0.6657; split: PetalLength<=2.450

001 - n_samples: 43; value: [43, 0, 0]; impurity: 0.0000

002 - n_samples: 77; value: [0, 39, 38]; impurity: 0.4999; split: PetalLength<=4.750

003 -- n_samples: 34; value: [0, 34, 0]; impurity: 0.0000

004 -- n_samples: 43; value: [0, 5, 38]; impurity: 0.2055; split: PetalWidth<=1.750

005 --- n_samples: 7; value: [0, 4, 3]; impurity: 0.4898; split: SepalWidth<=2.650

006 ---- n_samples: 3; value: [0, 1, 2]; impurity: 0.4444

007 ---- n_samples: 4; value: [0, 3, 1]; impurity: 0.3750

008 --- n_samples: 36; value: [0, 1, 35]; impurity: 0.0540; split: SepalLength<=5.950

009 ---- n_samples: 5; value: [0, 1, 4]; impurity: 0.3200

010 ---- n_samples: 31; value: [0, 0, 31]; impurity: 0.0000The value is the number of samples in each class in that node. The impurity is a measure of the mix of classes in the node. A pure node has only 1 type of class and 0 impurity. More will be explained on this later. The split is the rule for determining which values go to the left or right child. For example, the first split is almost the same as the first rule in the baseline model.

Universal Bank loans

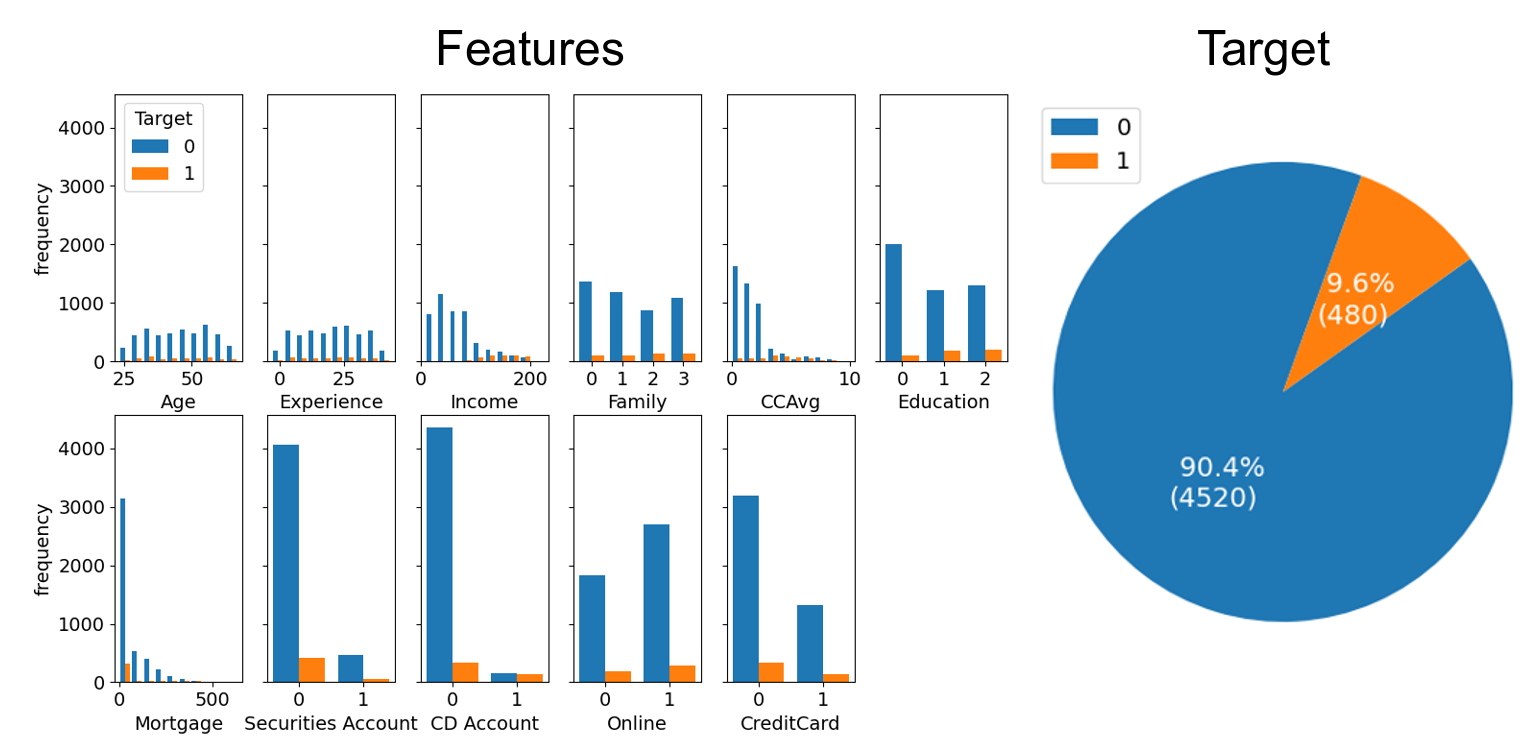

The next dataset I tested was the Bank_Loan_Classification dataset available on Kaggle at www.kaggle.com/sriharipramod/bank-loan-classification/. This dataset has 5000 entries with 11 features. The target variable is “Personal Loan”, and it can be 0 or 1. (Personal Loan approved? Or paid? I don’t know.)

The variable distributions are as follows:

The Pearson correlation coefficients between the features and the target variables are:

| Feature | Correlation | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Income | 0.5025 |

| 2 | CCAvg | 0.3669 |

| 3 | CD Account | 0.3164 |

| 4 | Mortgage | 0.1421 |

| 5 | Education | 0.1367 |

| 6 | Family | 0.0614 |

| 7 | Securities Account | 0.0220 |

| 8 | Experience | -0.0074 |

| 9 | Age | -0.0077 |

| 10 | Online | 0.0063 |

| 11 | CreditCard | 0.0028 |

For the baseline model, we could always predict a 0, and claim an accuracy of 90.4%. But this has an F1 score of 0.2 A better baseline is simply to have: 1 if Income > 100 else 0. This has an accuracy of 83.52% and a F1 score of 0.516 over the whole dataset.

I used my code to make a random forest classifier with the following parameters:

forest = RandomForestClassifier(n_trees=20, bootstrap=True, max_features=3, min_samples_leaf=3)

I randomly split the data into 4000 training samples and 1000 test samples and trained the forest on it.

The forest took about 10 seconds to train.

The trees range in depth from 11 to 17, with 51 to 145 leaves. The total number of leaves is 1609.

The training accuracy is 99.60% and the test accuracy is 98.70%. The F1 score for the test set is 0.926.

This is a large improvement on the baseline, especially for the F1 score.

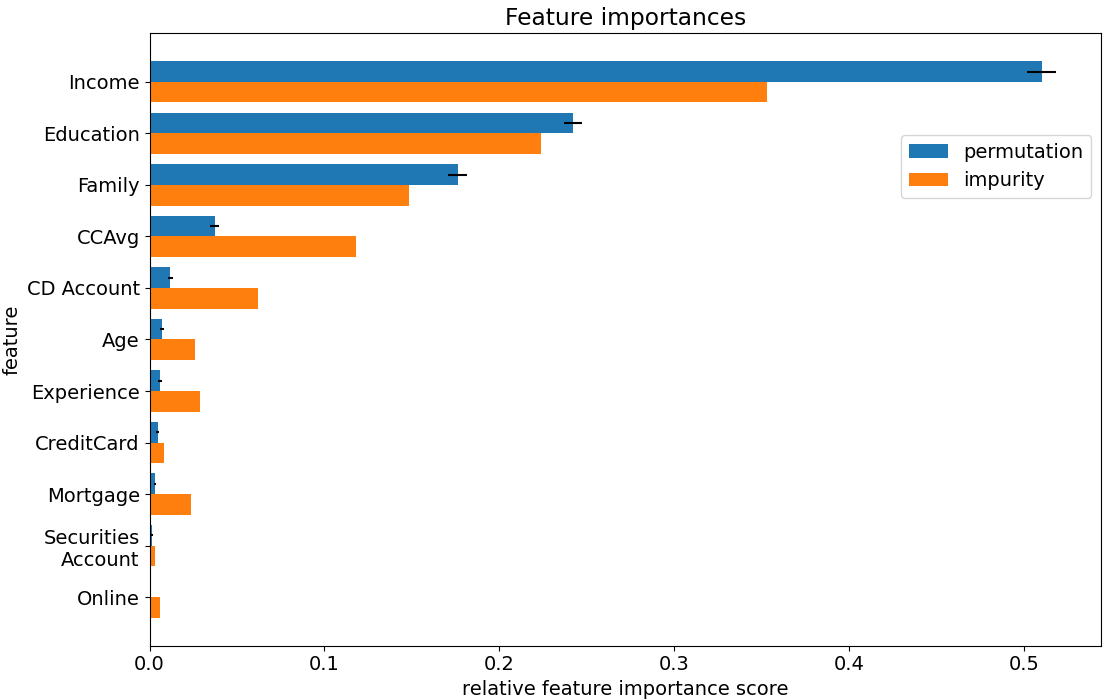

We can inspect the random forest and calculate a feature importance for each feature. The following graph is a comparison between two types of (normalised) feature importances. The orange bars are based on how much that feature contributes to decreasing the impurity levels in the tree. The blue bars are based on randomly scrambling that feature column, and recording how much this decreases the overall accuracy of the model. More detail on these calculations will be given later.

Code

RandomForestClassifier

The first step is create the RandomForestClassifier. Initialising an instance of the class only sets the internal parameters and does not fit the data,

as with the equivalent Scikit-learn class. I’ve included the most important parameters from Scikit-learn, and added one of my own, sample_size.3

This parameter sets the sample size used to make each tree. If bootstrap=False, it will randomly select a subset of unique samples for the training dataset.

If bootstrap=True, it will randomly draw samples with replacement from the dataset, which will most likely result in duplicate samples.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import warnings

from DecisionTree import DecisionTree

from utilities import *

class RandomForestClassifier:

def __init__(self, n_trees=100, random_state=None, max_depth=None,

max_features=None, min_samples_leaf=1, sample_size=None,

bootstrap=True, oob_score=False):

self.n_trees = n_trees

self.RandomState = check_RandomState(random_state)

self.max_depth = max_depth

self.max_features = max_features

self.min_samples_leaf=min_samples_leaf

self.sample_size = sample_size

self.bootstrap = bootstrap

self.oob_score = oob_scoreI’ve shown the imports for two internal modules, DecisionTree which I’ll describe later, and utilities, which imports some useful functions.

Many of those are also part of the Sklearn package; I just wanted my code to be completely independent.

If you wish to see these, have a look at the Github repository

The supervised learning is done by calling the fit() function.

First it internally one-hot encodes the target variable Y, which makes it easier to deal with multiple categories.

Then it creates the trees one at a time.

Most of the heavy lifting is done by other functions.

Afterwards, it sets attributes including the feature importances and the out-of-bag (OOB) score.

The random state is saved before each tree is made, because this can be used to exactly regenerate the random indices for the OOB score.

This is much more memory efficient than saving the whole list of random indices for each tree.

def fit(self, X, Y):

if Y.ndim == 1:

Y = encode_one_hot(Y) # one-hot encoded y variable

# set internal variables

self.n_features = X.shape[1]

self.n_classes = Y.shape[1]

self.features = X.columns

n_samples = X.shape[0]

self.sample_size_ = n_samples if self.sample_size is None else self.sample_size

# create decision trees

self.trees = []

rng_states = [] # save the random states to regenerate the random indices for the oob_score

for i in range(self.n_trees):

rng_states.append(self.RandomState.get_state())

self.trees.append(self._create_tree(X, Y))

# set attributes

self.feature_importances_ = self.impurity_feature_importances()

if self.oob_score:

if not (self.bootstrap or (self.sample_size_<n_samples)):

warnings.warn("out-of-bag score will not be calculated because bootstrap=False")

else:

self.oob_score_ = self.calculate_oob_score(X, Y, rng_states)The _create_tree() function is called by fit(). It randomly allocates samples, and creates a DecisionTree with the same parameters as the RandomForestClassifier.

It then passes the heavy lifting to the DecisionTree’s fit() function.

def _create_tree(self, X, Y):

assert len(X) == len(Y), ""

n_samples = X.shape[0]

# get sub-sample

if self.bootstrap: # sample with replacement

rand_idxs = self.RandomState.randint(0, n_samples, self.sample_size_)

X_, Y_ = X.iloc[rand_idxs, :], Y[rand_idxs] #

elif self.sample_size_ < n_samples: # sample without replacement

rand_idxs = self.RandomState.permutation(np.arange(n_samples))[:self.sample_size_]

X_, Y_ = X.iloc[rand_idxs, :], Y[rand_idxs]

else:

X_, Y_ = X.copy(), Y.copy() # do nothing to the data

new_tree = DecisionTree(max_depth=self.max_depth,

max_features=self.max_features,

random_state=self.RandomState,

min_samples_leaf=self.min_samples_leaf

)

new_tree.fit(X_, Y_)

return new_treeThe prediction of the forest is done through majority voting. In particular, a ‘soft’ vote is done, where each tree’s vote is weighted by its probability prediction per class. The final prediction is therefore equivalent to the class with the maximum sum of probabilities.

def predict(self, X) -> np.ndarray:

probs = np.sum([t.predict_prob(X) for t in self.trees], axis=0)

return np.nanargmax(probs, axis=1)

def score(self, X, y) -> float:

y_pred = self.predict(X)

return np.mean(y_pred==y)If bootstrap=True and/or the sample size is less than the total training set size , that means each tree is only trained on a subset of the data.

The out-of-bag score can then be calculated as the prediction for each sample based on the trees it was not used to train.

It is a useful measure of the accuracy of the training.

For sampling with replacement, where the sample size is the size of the dataset, we can expect on average 63.2% of samples to be unique.4

This means that per tree 36.8% samples are out-of-bag and can be used to calculate the OOB score.

def calculate_oob_score(self, X, Y, rng_states):

n_samples = X.shape[0]

oob_prob = np.zeros(Y.shape)

oob_count = np.zeros(n_samples)

rng = np.random.RandomState()

# regenerate random samples using the saved random states

for i, state in enumerate(rng_states):

rng.set_state(state)

if self.bootstrap: # sample with replacement

rand_idxs = rng.randint(0, n_samples, self.sample_size_)

else: #self.sample_size_ < n_samples, # sample without replacement

rand_idxs = rng.permutation(np.arange(n_samples))[:self.sample_size_]

row_oob = np.setxor1d(np.arange(n_samples), rand_idxs)

oob_prob[row_oob, :] += self.trees[i].predict_prob(X.iloc[row_oob])

oob_count[row_oob] += 1

# remove nan-values: these samples were never out-of-bag. Highly unlikely for n>6

valid = oob_count > 0

oob_prob = oob_prob[valid, :]

oob_count = oob_count[valid][:, np.newaxis] # transform to column vector for broadcasting during the division

y_test = np.argmax(Y[valid], axis=1)

# predict out-of-bag score

y_pred = np.argmax(oob_prob/oob_count, axis=1)

return np.mean(y_pred==y_test)The final function in RandomForestClassifier calculates the impurity based feature importance. It does so by finding the mean of the feature importances in each tree.

The detail behind these will be delayed to the next section.

def impurity_feature_importances(self) -> np.ndarray:

feature_importances = np.zeros((self.n_trees, self.n_features))

for i, tree in enumerate(self.trees):

feature_importances[i, :] = tree.feature_importances_

return np.mean(feature_importances, axis=0)DecisionTree

Each DecisionTree is a stand-alone estimator. Most of the complexity is actually in this class. So far, the RandomForestClassifier has mostly accumulated the results of it.

class DecisionTree:

def __init__(self, max_depth=None, max_features=None, min_samples_leaf=1, random_state=None):

self.max_depth = max_depth

self.max_features = max_features

self.min_samples_leaf = min_samples_leaf

self.RandomState = check_RandomState(random_state)

# initialise internal variables

self.tree_ = BinaryTree()

self.n_samples = []

self.values = []

self.impurities = []

self.split_features = []

self.split_values = []

self.size = 0 # current node = size - 1

def split_name(self, node_id: int) -> str:

return self.features[self.split_features[node_id]]The important variables are stored in arrays. The binary tree structure is stored in a separate class, BinaryTree. A node ID is used to retrieve elements from the BinaryTree. As long as we keep track of these node IDs, we can fully abstract the complexity of the BinaryTree.

The fit function is again separate to initialisation.

It starts a recursive call to _split_node() which grows the tree until a stopping criterion is reached.

def fit(self, X, Y):

if Y.ndim == 1:

Y = encode_one_hot(Y) # one-hot encoded y variable

# set internal variables

self.n_features = X.shape[1]

self.n_classes = Y.shape[1]

self.features = X.columns

self.max_depth_ = float('inf') if self.max_depth is None else self.max_depth

self.n_features_split = self.n_features if self.max_features is None else self.max_features

# initial split which recursively calls itself

self._split_node(X, Y, 0)

# set attributes

self.feature_importances_ = self.impurity_feature_importance()The function _split_node() does many different actions:

- Increases the sizes of the internal arrays and BinaryTree.

- Calculates the values and impurity of the current node.

- Randomly allocates a subset of features. Importantly, this is different per split. If the whole tree was made from the same subset of features, it is likely to be 'boring' and not that useful.

- Makes a call to `_find_better_split()` to determine the best feature to split the node on. This is a greedy approach because it expands the tree based on the best feature right now.

- Creates children for this node based on the best feature for splitting.

def _set_defaults(self, node_id: int, Y):

val = Y.sum(axis=0)

self.values.append(val)

self.impurities.append(gini_score(val))

self.split_features.append(None)

self.split_values.append(None)

self.n_samples.append(Y.shape[0])

self.tree_.add_node()

def _split_node(self, X, Y, depth: int):

node_id = self.size

self.size += 1

self._set_defaults(node_id, Y)

if self.impurities[node_id] == 0: # only one class in this node

return

# random shuffling removes any bias due to the feature order

features = self.RandomState.permutation(self.n_features)[:self.n_features_split]

# make the split

best_score = float('inf')

for i in features:

best_score = self._find_bettersplit(i, X, Y, node_id, best_score)

if best_score == float('inf'): # a split was not made

return

# make children

if depth < self.max_depth_:

x_split = X.values[:, self.split_features[node_id]]

lhs = np.nonzero(x_split<=self.split_values[node_id])

rhs = np.nonzero(x_split> self.split_values[node_id])

self.tree_.set_left_child(node_id, self.size)

self._split_node(X.iloc[lhs], Y[lhs[0], :], depth+1)

self.tree_.set_right_child(node_id, self.size)

self._split_node(X.iloc[rhs], Y[rhs[0], :], depth+1)_find_better_split() is the main machine learning function. It is not surprisingly the slowest function in this code and the main bottleneck for performance.

The first question to answer is, what is considered a good split? For this, the following simpler, related problem is used as a proxy:

if we were to randomly classify nodes, but do so in proportion to the known fraction of classes, what is the probability we would be wrong?

Of course, we are not randomly classifying nodes - we are systematically finding the best way to do so.

But it should make intuitive sense that if we make progress on the random problem, we make progress on the systematic problem.

If we make a good split that mostly separates the classes and then randomly classify them, we would make fewer mistakes.

For a class $k$ with $n_k$ samples amongst $n$ total samples, the probability of randomly classifying that class wrongly is:

\[\begin{align} P(\text{wrong classification} | \text{class k}) &= P(\text{select from class k})P(\text{classify not from class k}) \\ &= \left(\frac{n_k}{n} \right) \left(\frac{n-n_k}{n}\right) \end{align}\]Summing these probabilities for all classes gives the supremely clever Gini impurity:

\[Gini = \sum^K_{k=1} \left(\frac{n_k}{n} \right) \left(1 - \frac{n_k}{n}\right) = 1 -\sum^K_{k=1} \left(\frac{n_k}{n} \right)^2\]The lower the Gini impurity, the better the split. To determine the best split, we sum the Gini impurities of the left and right children nodes, weighted by the number of samples in each node. We then minimise this weighted value.

The second question is, how do we find a value to split on? Well, a brute force approach is to try a split at every sample with a unique value. This is not necessarily the most intelligent way to do things.5 But it is the most generic and works well for many different scenarios (few unique values, many unique values, outliers etc). So it is the most commonly used tactic.

def gini_score(counts): return 1 - sum([c*c for c in counts])/(sum(counts)*sum(counts))

def _find_bettersplit(self, var_idx: int, X, Y, node_id: int, best_score: float) -> float:

X = X.values[:, var_idx]

n_samples = self.n_samples[node_id]

# sort the variables.

order = np.argsort(X)

X_sort, Y_sort = X[order], Y[order, :]

# Start with all on the right. Then move one sample to the left one at a time

rhs_count = Y.sum(axis=0)

lhs_count = np.zeros(rhs_count.shape)

for i in range(0, n_samples-1):

xi, yi = X_sort[i], Y_sort[i, :]

lhs_count += yi; rhs_count -= yi

if (xi == X_sort[i+1]) or (sum(lhs_count) < self.min_samples_leaf):

continue

if sum(rhs_count) < self.min_samples_leaf:

break

# Gini Impurity

curr_score = (gini_score(lhs_count) * sum(lhs_count) + gini_score(rhs_count) * sum(rhs_count))/n_samples

if curr_score < best_score:

best_score = curr_score

self.split_features[node_id] = var_idx

self.split_values[node_id]= (xi + X_sort[i+1])/2

return best_scoreMaking $m$ splits will result in $m+1$ leaf nodes (think about it). The tree therefore has $2m+1$ nodes in total, and $2m$ parameters (a feature and value per split node).

After the tree is made, we can make predictions by filtering down samples through the tree. The image at the top of this page shows a schematic of this.

The original method from the FastAI course was to filter each sample row by row. I found it is quicker to filter several rows at a time.

The first batch of rows is split into two based on the current node split value.

Then each batch is sent to a different recursive call of _predict_batch().

In the worst case, this will reduce to filtering by each row if each sample lands in a different final leaf.

But if many samples end up in the same leaf, which is guaranteed if the dataset is larger than the number of leaves, than this method is faster because of Numpy indexing.

def _predict_batch(self, X, node=0):

if self.tree_.is_leaf(node):

return self.values[node]

if len(X) == 0:

return np.empty((0, self.n_classes))

left, right = self.tree_.get_children(node)

lhs = X[:, self.split_features[node]] <= self.split_values[node]

rhs = X[:, self.split_features[node]] > self.split_values[node]

probs = np.zeros((X.shape[0], self.n_classes))

probs[lhs] = self._predict_batch(X[lhs], node=left)

probs[rhs] = self._predict_batch(X[rhs], node=right)

return probs

def predict_prob(self, X):

probs = self._predict_batch(X.values)

probs /= np.sum(probs, axis=1)[:, None] # normalise along each row (sample)

return probs

def predict(self, X):

probs = self.predict_prob(X)

return np.nanargmax(probs, axis=1)The last major function is the calculation for the impurity based feature importances. For each feature, it can be defined as: the sum of the (weighted) changes in impurity between a node and its children at every node that feature is used to split. In mathematical notation:

\[FI_f = \sum_{i \in split_f} \left(g_i - \frac{g_{l}n_{l}+g_{r}n_{r}}{n_i} \right) \left( \frac{n_i}{n}\right)\]Where $f$ is the feature under consideration, $g$ is the Gini Impurity, $i$ is the current node, $l$ is its left child, $r$ is its right child, and $n$ is the number of samples.

The weighted impurity scores from _find_better_split() need to be recalculated here.

def impurity_feature_importance(self):

feature_importances = np.zeros(self.n_features)

total_samples = self.n_samples[0]

for node in range(len(self.impurities)):

if self.tree_.is_leaf(node):

continue

spit_feature = self.split_features[node]

impurity = self.impurities[node]

n_samples = self.n_samples[node]

# calculate score

left, right = self.tree_.get_children(node)

lhs_gini = self.impurities[left]

rhs_gini = self.impurities[right]

lhs_count = self.n_samples[left]

rhs_count = self.n_samples[right]

score = (lhs_gini * lhs_count + rhs_gini * rhs_count)/n_samples

# feature_importances = (decrease in node impurity) * (probability of reaching node ~ proportion of samples)

feature_importances[spit_feature] += (impurity-score) * (n_samples/total_samples)

return feature_importances/feature_importances.sum() There is another simpler method to calculate feature importance: shuffle (permutate) a feature column, and record how well the model performs.

Shuffling a column makes the values for each sample random, but at the same time keeps the overal distribution for the feature constant.

Scikit-learn has a great article on the advantages of this over impurity based feature importance.

(A perm_feature_importance() function is in the utilities.py module.)

BinaryTree

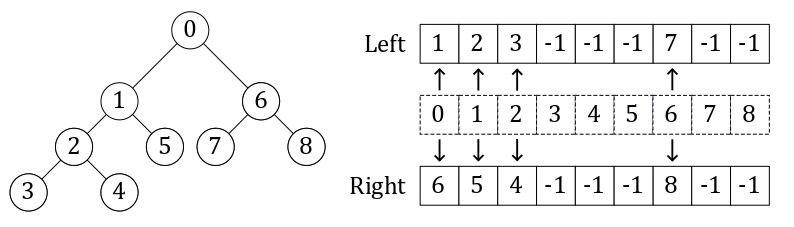

The most direct way to code a binary tree is to do so as a linked list. Each node is an object with pointers to its children. This was the method originally used in the FastAI course. The method that Scikit-learn uses, and that I chose to use, is to encode it as a set of two parallel lists. The image above shows an example of this representation. The index is the node ID, and the values in the left and right array are the node IDs (indexes) for that node’s children. If the value is -1, it means this node has no children and is a leaf. This method is more compact than the linked list, and has an O(1) look-up time for children given a node ID.

This is the smallest and simplest class, and so I will present the entire code here without further explanation:

class BinaryTree():

def __init__(self):

self.children_left = []

self.children_right = []

@property

def n_leaves(self):

return self.children_left.count(-1)

def add_node(self):

self.children_left.append(-1)

self.children_right.append(-1)

def set_left_child(self, node_id: int, child_id: int):

self.children_left[node_id] = child_id

def set_right_child(self, node_id: int, child_id: int):

self.children_right[node_id] = child_id

def get_children(self, node_id: int) -> Tuple[int]:

return self.children_left[node_id], self.children_right[node_id]

def is_leaf(self, node_id: int) -> bool:

return self.children_left[node_id] == self.children_right[node_id] #==-1Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed this post, and that it clarified the inner workings of a random forest. If you would like to know more, I again recommend Jeremy Howard’s FastAI course. He explains the rational behind random forests, more on tree interpretation and more on the limitations of random forests.

What did you think of the top-down approach? I think it works very well.

In the future, I would like to investigate more advanced versions of tree ensembles, in particular gradient boosting techniques like CatBoost.

-

Don’t know what a sepal is? I didn’t either. It’s the outer part of the flower that encloses the bud. Basically it’s a leaf that looks like a petal. ↩

-

The F1 score balances recall (fraction of true positives predicted) with precision (fraction of correct positives). Guessing all true would have high recall but low precision. It is better to have both. $F1 =\frac{2}{\frac{1}{\text{recall}}+\frac{1}{\text{precision}}}$ ↩

-

It is annoying that the Scikit-learn module does not include this parameter. There are ways around it. For example the FastAI package edits the Scikit-learn code with

set_rf_samples(). Or you could sample data yourself and train a tree one at a time using thewarm_start=Trueparameter. But these are hacks for what I think could have been a simple input parameter. ↩ -

Let the sample size be k and the total number of samples be n. Then the probability that there is at least one version of any particular sample is: \(\begin{align} P(\text{at least 1}) &= P(\text{1 version}) + P(\text{2 versions}) + .... + P(k \text{ versions}) \\ &= 1 - P(\text{0 versions}) \\ &= 1 - \left (\frac{n-1}{n} \right)^k \\\underset{n \rightarrow \infty}{lim} P(\text{at least 1}) &= 1 - e^{-k/n}\\\end{align}\).

For n=k, $P(\text{at least 1})\rightarrow 1-e^{-1} = 0.63212…$ ↩ -

Another way would probably be to determine the distribution of values e.g. linear, exponential, categorical. Then use this information to create a good feature range. ↩