I recently solved a particular kind of puzzle, nonograms, using finite state machines for regex matching. This is a very efficient way to do regex matching and in fact formed the basis of the first regex matchers. Finite state machines have since been replaced with more versatile but slower backtracking algorithms. Here is one case however where the older method works better.

Update 3 December 2022: edits to the text and updated the code.

Introduction

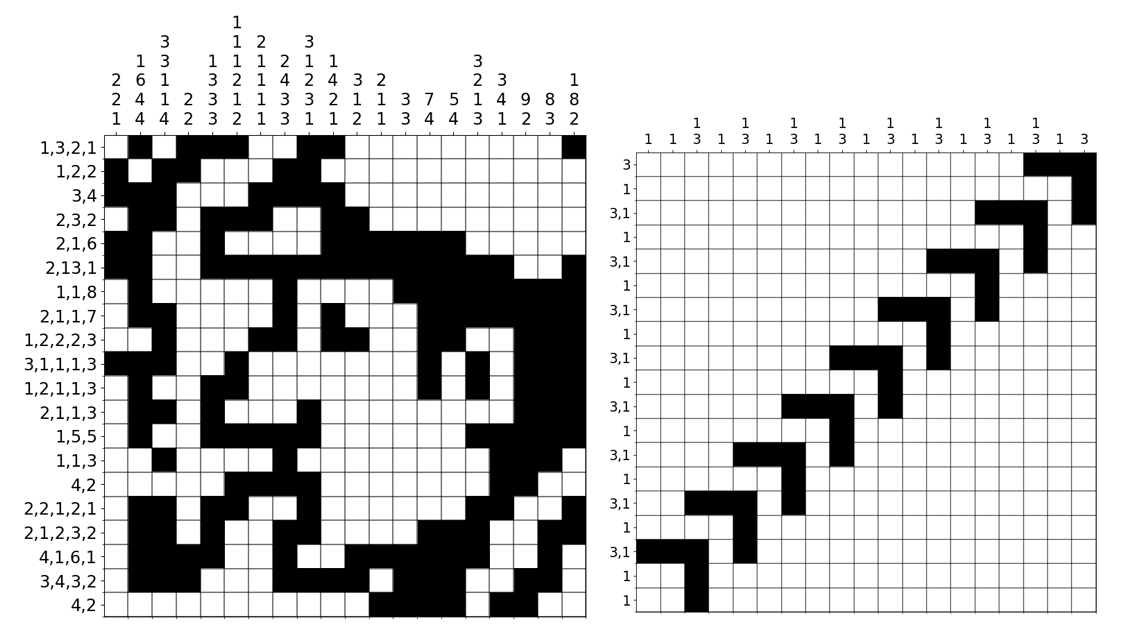

I recently got hooked on a new type of puzzle, nonograms. Wikipedia has a great entry explaining them here. Here is a small example:

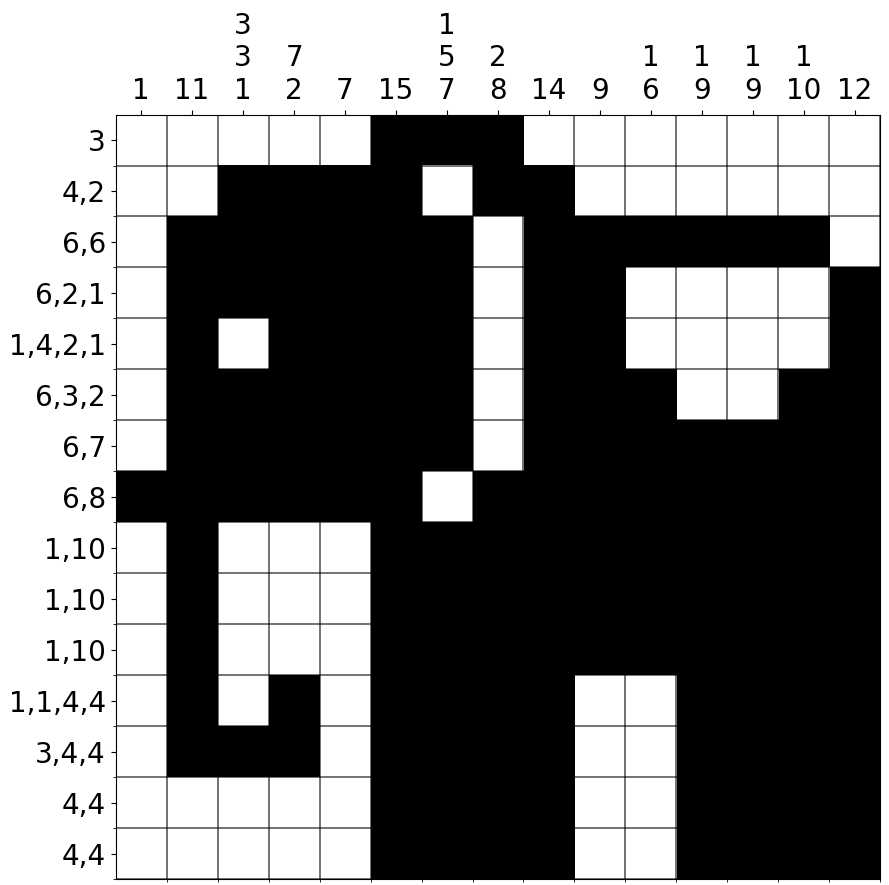

Each puzzle consists of a grid with numbers along the rows and columns. These numbers indicate connected sets of shaded cells along that row/column, with an unknown amount of unshaded cells in between. For example, the clue (4, 2) along row 2 means that in this row there are an unknown number of white cells, followed by 4 shaded cells, followed by one or more white cells, followed by 2 shaded cells, and then another unknown number of white cells. The aim is to shade the cells so that all clues read correctly. Puzzles have the added bonus that they are designed to result in a picture. For example, here is the unique solution to the above puzzle:

I wrote solvers for these puzzles in both C++ and Python. Of course, such a problem is already well investigated. See Jan Wolter’s survey of online solvers. My solvers are actually rather slow compared to some of those. It takes more than a minute for some puzzles, where as Jan claims his own solver took a second. See also Rosetta code’s collection of brute force solvers in many different languages. These solvers are slow but will always solve the puzzle.

This problem shares many characteristics with Sudoku, which I covered in a previous blog post. Like Sudoku, the puzzle involves a grid and the general problem is NP complete. Also like Sudoku, many puzzles are designed with the intention of having a unique solution, but there is no guarantee for this. Lastly, the most efficient way to solve it is through constraint propagation, but if you get stuck guessing is the simplest way forward.

Unlike my Sudoku post, I am not going to fully describe the solvers here. Instead, I would like to concentrate on one particular aspect of the solver, pattern matching. I think this is the most valuable part of the solver, because this technique is transferable to many other situations.

How to solve nonograms

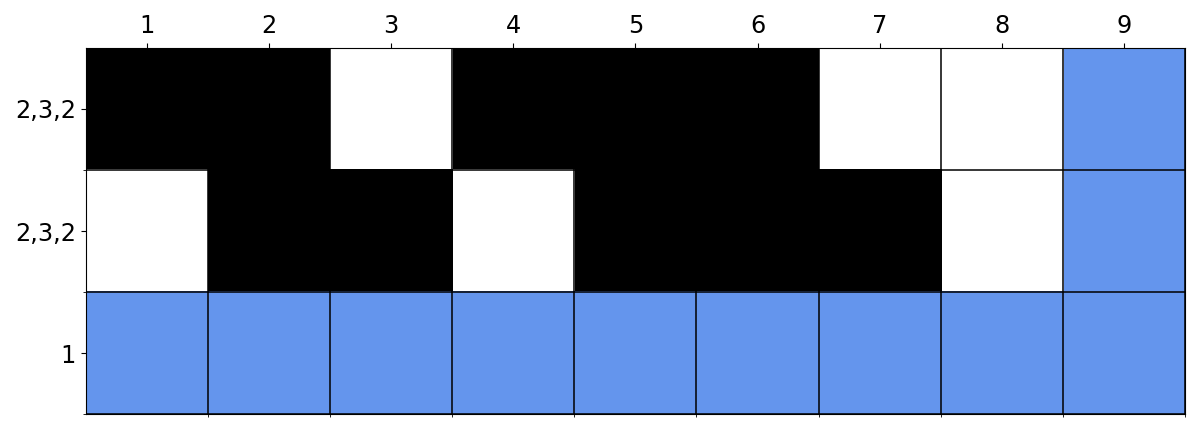

A blank nonogram puzzle can be daunting. Thankfully there is a simple technique to get going. For every row/column, construct the left-most/top-most solution. Then slide it across all the way to the right/bottom. The cells that always remain part of the same sequence (whether black or white) can be shaded in.

For example, for the above nonogram:

Row 6 with the run (6,3,2) is the row of interest. Rows 5 and 7 show the left-most and right-most solutions respectively (and not solutions for row 5 or 7). The shaded cells in row 6 are the cells that always overlap in row 5 and row 7. These can be kept black, and all other cells should be left unknown.

This process is then completed for every row. Next, it is done for each column, except this time the solution is constrained by the cells already shaded in each row. This process can then be repeated on each row with the new constraints. And so on. For many puzzles, the entire puzzle can be solved with this one technique alone.

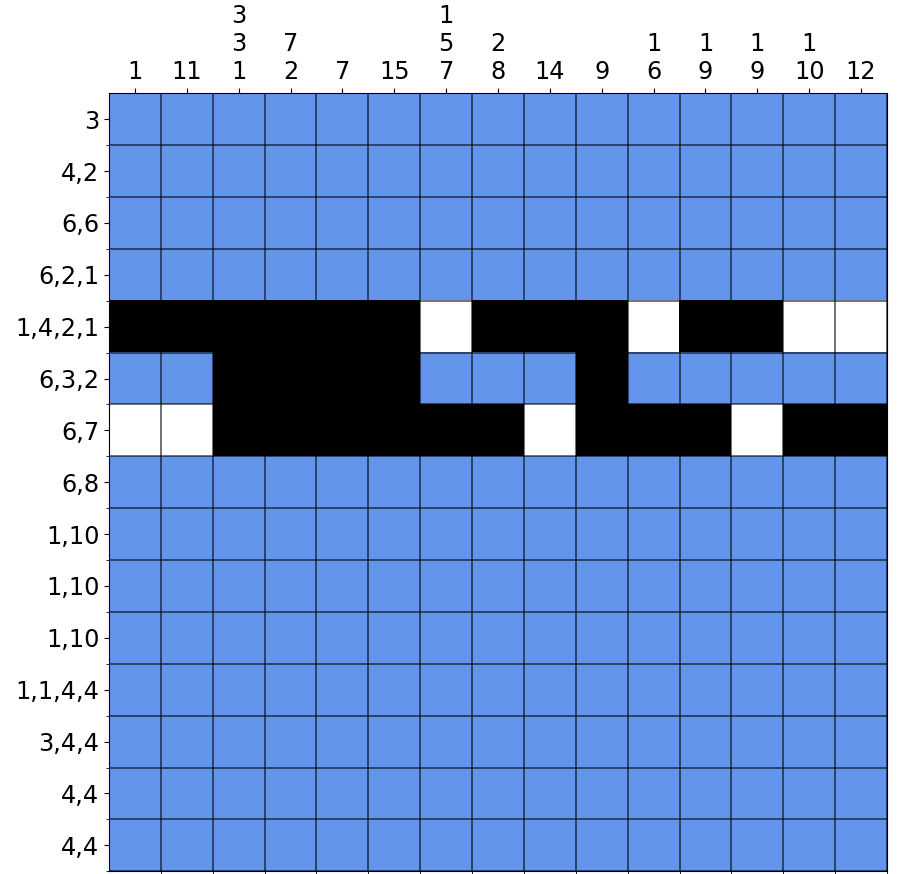

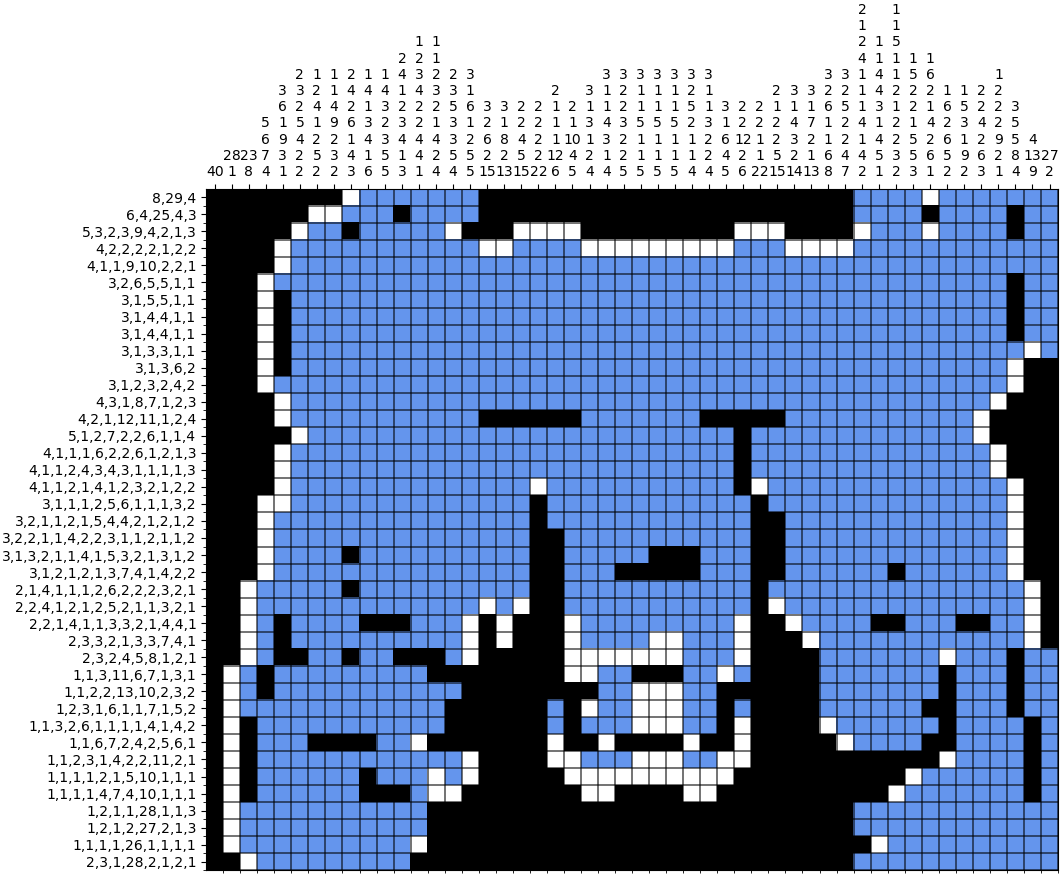

Before continuing, I would like to showcase examples where this fails. The first is this aeroplane puzzle:

In the left image, the left-right matcher algorithm has got stuck. But this puzzle can still be solved with other logic. Notably, two white blocks in the middle are always white regardless of which sequence the single blacks in the corresponding rows belong too. This unlocks the rest of the puzzle. It is not obvious - in fact in the source video, the guy resorts to guessing.

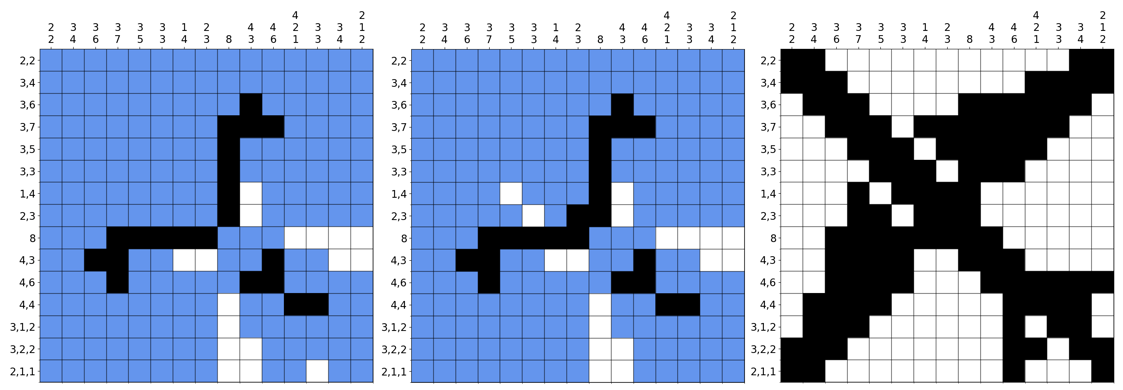

The next two puzzles are more challenging. Both consist of many small black runs with plenty of white space:

At first logic line solving will not get you anywhere with these puzzles. But a few guesses will unlock them. A caveat though with “Domino Logic III” - a string of bad guesses can lead down a seemingly never ending path of guesses.

Regex and nondeterministic finite state automata

The trickiest part of the left-right algorithm is finding the left-most match.1 For an empty puzzle, this is trivial. However as more cells are shaded and the puzzle gets larger, this gets harder. See for example the above half finished puzzle (final solution). The main difficulty comes from deciding whether to place a white or not. This binary choice leads to $\mathcal{O}(2^n)$ complexity. I originally implemented a depth-first search (DFS) with backtracking, but for large puzzles (100x100) this was too slow. This was especially crippling on puzzles which required guessing, which adds another layer of backtracking.

We shouldn’t need to explore each binary choice though. There is plenty of overlap between solutions and it should be possible to exclude many of them. For example, if we can quickly establish that the first cell is always black we can exclude all possibilities where it is white. I tried to write heuristics for this but my algorithms always seemed to turn into DFS. So I looked around for more efficient matching algorithms and came across this blog post by Russ Cox. It describes Ken Thompson’s $\mathcal{O}(n^2)$ matching algorithm for regular expressions using nondeterministic finite state automata (NFA).

The important insight was that this nonogram problem, like the regex problem, is mostly dependent on the active state. Multiple different paths can converge to the same state and once they do they are collapsed into one. This significantly reduces the amount of possibilities and the complexity of the algorithm. For example, here at column 8 both these two paths are white after two black runs and hence they are in the same state. After this point, these two will be indistinguishable from each each other. (We can keep track of which path is the left-most match separately.)

In order to the reuse Thompson’s matching algorithm we first need to rephrase the nonogram problem as a regex problem. This is done as follows:

- Take a run (a, b, …, z).

- Use binary encoding for each of the three colours:

- black cell: $01_2 = 1$

- white cell: $10_2 = 2$

- either: $11_2 = 3$

- The starting Nonogram number $a$ corresponds to zero or more whites followed by $a$ blacks followed by one or more whites. In regex notation:

(2)*(1){a}(2)+. - Account for cells that are unknown (either):

([23]*)([13]){a}([23]+). - Repeat for pairs of blacks and whites in the middle:

([13]){b}([23]+)... - The last cell can be followed by an unknown number of whites:

([13]){z}([23]*)

The run (a, b, …, z) thus becomes the pattern: ([23]*)([13]){a}([23]+)([13]){b}([23]+)...([13]){z}([23]*).

Regex matchers themselves are usually DFS algorithms. For the most part this is more practical than finite state automata. DFS allows more complex regular expressions (Cox’s article has a full list). However the exponential nature of backtracking can cause them to fail, sometimes in spectacular fashion.

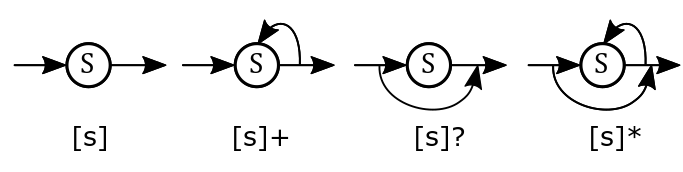

An alternative is to represent the character expression as a nondeterministic finite state automation. Let’s break that name down:

- Automation: a sort of machine/program. I find the term archaic but it does come from a time before computers.

- Finite state: there is a countable number of states. This is opposed to infinite or continuous states, such as measurements with gradients in nature, or states which depend on such a large combination of elements that they are for practical purposes uncountable.

- Nondeterministic: given a state, it cannot always be determined what the previous state was. Actually, that is a minor problem here because we do want to know how many times we have passed through each state, not just the current state. But we can store this information outside of the NFA.

The NFA is composed of states S which transition in one of the following ways:

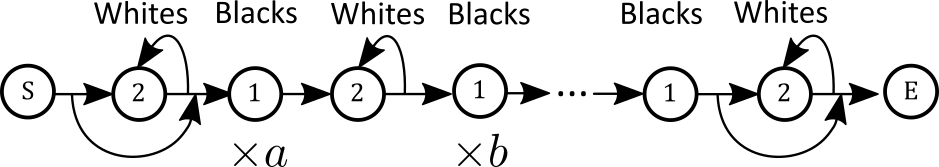

We can use these components to build up a full state automation for our regex pattern:

We start at the start state S and as we read characters transition to the right. We only transition if the next character matches the next state. If the next character doesn’t match any transition, then we halt the matching process.

If we were to backtrack on a halt, then this algorithm would still be an $\mathcal{O}(2^n)$ process. It is made into an $O(n^2)$ algorithm by doing the following:

- At each split with multiple valid transitions, simultaneously do all.

- Only keep track of current active states. As discussed above, this collapses paths into a finite number of states.

The number of active states is purely a function of the pattern length. That is $O(n)$. So since we process $n$ characters, the whole algorithm is $O(n^2)$.

The minor difficulty is that we do want to keep track of at least one path - the left-most match. We can do this by keeping track of one path per state. In the case that we get two or more paths converging to the same state - as in the image above - we’ll always take preference for a state that is repeating, because that is a more left-most match. So for the example the first row with a repeating white is saved. Otherwise, we’ll take preference for the path of the first state that enters a new state. When we finish the NFA for the first time we return the path that is associated with it.

Code

This is my C++ code for the NFA matcher. For the full code, see my Github repository.

Firstly, three types of objects are defined in the header: Match, State and NonDeterministicFiniteAutomation:2

struct Match

{

vector<int> match{};

vector<int> pattern{};

bool is_match {false};

};

struct State

{

char symbol = '\0';

int id = 0; // position in the NFA list

char qualifier = '\0'; // purely for descriptive purposes

bool is_end = false;

vector<int> transitions; // states that this transitions to

};

class NonDeterministicFiniteAutomation

{

public:

NonDeterministicFiniteAutomation(){};

void compile(vector<int> pattern_); //convert a numerical pattern to a regex pattern

Match find_match(vector<int>& array); //returns the left-most match

vector<State> change_state(State &state, char in_symbol);

private:

vector<State> states;

vector<int> pattern;

int num_states{0}; // also used to determine the state ids

bool is_compiled{false};

vector<char> convert_pattern(vector<int> pattern);

};The first step is to compile the pattern to a finite state machine.

This is tricky because of potential nested expressions and also because of skipping states (e.g. with ? or *).

The Thompson construction first converts the pattern to postfix notation.

It then uses a stack to keep track of the start and end states.

For my implementation here, I’ve stored all the states in the vector states and the stack holds the indices of each state in that vector.

These indices are referred to as “state IDs” in the code.

Then depending on the input symbol, a different action is taken.

vector<char> NonDeterministicFiniteAutomation::convert_pattern(vector<int> pattern)

{

vector<char> fragments;

fragments.push_back(BLANK); //implicit conversion to char

fragments.push_back('*');

for (int p: pattern){

for (int i{0}; i<p; i ++){

fragments.push_back(BOX);

fragments.push_back('.');

}

fragments.push_back(BLANK);

fragments.push_back('+');

fragments.push_back('.');

}

// the final blank is not checked in the NFA

fragments.pop_back(); // remove .

fragments.pop_back(); // remove +

fragments.pop_back(); // remove BLANK

return fragments;

}

void NonDeterministicFiniteAutomation::compile(vector<int> pattern_)

{

/* convert a numerical sequence such as (a, b, ..) to regex.

e.g. (1,5,3) -> ([23]*)([13]){1}([12]+)([13]){5}([12]+)([13]){3}([12]+)([23]*) */

//reset

this->pattern = pattern_;

num_states = 0;

is_compiled = false;

this->states = {};

// add start and end to state list

State start {'\0', num_states++, 's'};

states.push_back(start);

State end {'\0', num_states++}; //continuously update the end

states.push_back(end);

// match an empty pattern

if (pattern.size() == 0){

states[1].is_end = true;

states[1].symbol = BLANK; //

states[0].transitions.push_back(1);

is_compiled = true;

return;

}

//general case

stack<int> st; // state ids to modify

st.push(0); // add start to the stack

st.push(1); // add end to the stack

int next_, state, prev_; // always work with these 3 states. Underscore because next and prev are std keywords

vector<char> fragments = convert_pattern(pattern);

for (char sym: fragments){

State new_end; // only used for "default"

switch (sym){

case '+': // one or more

next_ = st.top(); st.pop();

state = st.top();

this->states[state].qualifier = '+';

this->states[state].transitions.push_back(state); //loop back on itself

st.push(next_);

break;

case '*': //zero or more.

next_ = st.top(); st.pop();

state = st.top(); st.pop();

prev_ = st.top();

this->states[state].transitions.insert(this->states[state].transitions.begin(), next_); //normal catenation

this->states[state].transitions.push_back(state); //loop back on itself

this->states[state].qualifier = '*';

this->states[prev_].transitions.insert(this->states[prev_].transitions.begin(), state); //normal catenation

st.push(next_); //state is not added to the stack

break;

case '.': // catenation

next_ = st.top(); st.pop();

state = st.top(); st.pop();

prev_ = st.top(); // prev is kept on the stack as the start (in case of multiple consecutive *)

this->states[prev_].transitions.insert(this->states[prev_].transitions.begin(), state);

st.push(state);

st.push(next_);

break;

default: // a number

next_ = st.top();

this->states[next_].symbol = sym;

new_end.id = num_states++;

st.push(new_end.id);

this->states.push_back(new_end);

}

}

this->states.pop_back(); // remove unnecessary end

states.back().is_end = true;

is_compiled = true;

} Next some helper functions:

bool is_finished(vector<int> &array, int idx)

{

for (int i = idx + 1; i < array.size(); ++i)

{

if (array[i] == BOX)

{

return false;

}

}

return true;

}

bool is_valid_transition(State &state, int bit)

{

return (state.symbol == '\0' || state.symbol & bit);

}

bool is_repeated_state(State *state, State *next_state)

{

return (next_state->id == state->id);

}

bool is_new_state(unordered_map<int, vector<int>> &matches, State *next_state)

{

return matches.find(next_state->id) == matches.end();

}

void fill_end_with_blanks(vector<int> &vec, int length)

{

vector<int> trailing_zeros(length - vec.size(), BLANK);

vec.insert(vec.end(), trailing_zeros.begin(), trailing_zeros.end());

}Then the simulation.

We cannot advance each state simultaneously, but this is very closely achieved by advancing each state one step at a time, one after the other. We store the active states in a hash table with the key being the state ID and the entry being the matching vector so far. The unique key property of the hash table guarantees that our current states are all unique. A duplicate state is either overwritten or not entered into the table.

A second hash table is used to make sure that the new transitions are all independent. That is, an old state is not overwritten because it was a new state for another state that should have advanced simultaneously with it, but happened to advance one step earlier.

Match NonDeterministicFiniteAutomation::find_match_(vector<int> &target)

{

if (!this->is_compiled)

{

throw "The NFA was not compiled!";

}

if (pattern.empty() && target.empty())

{

return Match{ {}, {}, true};

}

int idx = -1;

unordered_map<int, vector<int>> matches;

unordered_map<int, vector<int>> new_matches;

vector<int> empty_vec;

empty_vec.reserve(target.size());

matches.insert(pair<int, vector<int>>(0, empty_vec));

while (idx < (int)target.size() - 1 && !matches.empty())

{

++idx;

unordered_map<int, vector<int>>::iterator it;

for (it = matches.begin(); it != matches.end(); ++it)

{

int state_id = it->first;

vector<int> *match = &it->second;

State *state = &states[state_id];

for (int next_id : state->transitions)

{

if (is_valid_transition(this->states[next_id], target[idx]))

{

State *next_state = &states[next_id];

if (next_state->is_end)

{

if (is_finished(target, idx))

{

match->push_back(next_state->symbol);

fill_end_with_blanks(*match, target.size());

return Match{*match, this->pattern, true};

}

}

else if (is_new_state(new_matches, next_state)

|| is_repeated_state(state, next_state) // repeat states can overwrite new states

)

{

new_matches[next_state->id] = *match;

new_matches[next_state->id].push_back(next_state->symbol);

}

} // else skip this transition

} // move to the next transition

} // move to the next active state

matches.swap(new_matches);

new_matches.clear();

}

return Match{ {}, this->pattern, false}; // no match was found

}Example:

vector<int> string_to_vec(string line_str)

{

unordered_map<char, int> symbols2int;

symbols2int['-'] = BLANK;

symbols2int['#'] = BOX;

symbols2int[' '] = EITHER;

vector<int> line = {};

for (char c : line_str)

{

line.push_back(symbols2int[c]);

}

return line;

}

unique_ptr<NonDeterministicFiniteAutomation> nfa =

make_unique<NonDeterministicFiniteAutomation>();

vector<int> line;

vector<int> result;

Match m;

string s0 = "---#-- - # ";

string s1 = "---#--#-----------#####-";

string s2 = "---#-------------#-#####";

line = string_to_vec(s0);

result = string_to_vec(s1);

// left match

vector<int> pattern = {1, 1, 5};

nfa->compile(pattern);

m = nfa->find_match(line);

cout << (m.match == result) << "\n";

// right match

reverse(pattern.begin(), pattern.end());

nfa->compile(pattern);

reverse(line.begin(), line.end());

m = nfa->find_match(line);

reverse(m.match.begin(), m.match.end());

result = string_to_vec(s2);

cout << (m.match == result) << "\n";The output should be:

1 //true

1 //true

Conclusion

String matching with NFAs is a useful technique that I’m sure will come in handy in many different situations. It is understandable why more versatile DFS replaced them as the default algorithm for regex. The simplicity of NFAs is also their downfall - complex regex cannot be modelled with them. But certainly for cases like this which don’t have complex matching criteria, it is the superior option.

I’m still curious if there are faster ways to solve nonograms or to find a left-most match. Jan Wolter’s code for one was certainly faster than mine, and I am not sure why.

-

The right-most match can be found with the same algorithm by either iterating through the indices backwards, or passing a reversed version of the pattern and line to the left-most matcher. ↩

-

To make the code more readable, I’ve presented it as if I called

using namespace std. But according to best practice, I did not do this in the actual code. ↩