This post describes a Sudoku solver in Python. Even the most challenging Sudoku puzzles can be quickly and efficiently solved with depth first search and constraint propagation.

Update 13-03-2021: Erfan Paslar made a neat user interface for my solver using JavaScript and the Eel Python package. You can download the solver and UI code from my GitHub repository. Also head over to his own website for a tutorial on Eel. As an example of the UI, here is the solution for the 13 March 2021 NY Time’s Hard puzzle: solution.

Table of contents

1. Introduction

Recently the Sudoku bug bit me. According to Wikipedia, this popular brain teaser puzzle rose to prominence in 2004. “Sudoku” is Japanese for “single number”. The goal of Sudoku is to full a 9x9 grid where each row, column and 3x3 region contains each of the numbers from 1 to 9. These puzzles range in difficulty, and some can be surprisingly hard to solve by hand. But all are remarkably easy to solve with computers.

Other solvers

After a few days of manually playing Sudoku, I naturally decided to write a solver for it. I tackled this problem by myself, before comparing it to other online solvers.

There are two articles I would like to mention that were particularly helpful. The first article is by Ali Spittel. I liked the overall structure of her code, and used it to refactor some of mine. Her code however cannot solve hard puzzles because it only follows a simple constraint propagation strategy. The second article is by Peter Norvig. He uses a more comprehensive search and constraint propagation strategy and provides a thorough analysis with multiple puzzles. I used his set of 95 hard puzzles and 11 hardest puzzles to test my code. However, I found his structure unintuitive. For example, he stores the board as a dictionary instead of a 9x9 array.

Raghav Virmani’s augmented reality solver is very cool. This program solves and overlays solutions on pictures of unsolved Sudokus in real time. It does this by combining Norvig’s solver with a Convolutional Neural Network that can read pictures of numbers.

There are many solvers which refrain from search or any other trial and error strategies. One of the more complex of these is Andrew Stuart’s solver which implements 38 different strategies for solving Sudokus. A major drawback of this type of solver is, despite the complexity, it cannot solve every type of Sudoku puzzle.

2. Difficulty levels

Before describing my solver, I’d like to give a quick overview of difficulty levels in Sudoku. I’ve gained an appreciation of them over the last few weeks.

The difficulty levels are:

- Easy to Hard

- Very hard

- Ultra-hard

- Impossible

This is from a human viewpoint. Because the solver uses search, these levels don’t affect its performance. For a computer, all puzzles can be described as “easy”.

This section only considers puzzles with a unique solution or no solution. Any given Sudoku puzzle might have multiple solutions, but most published Sudokus only have one. My solver can find all solutions for any given puzzle.

Easy to hard puzzles

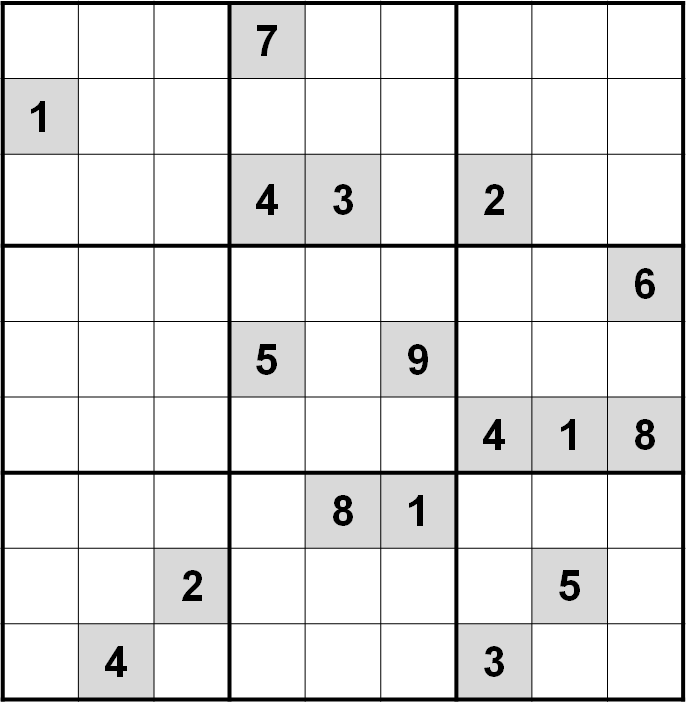

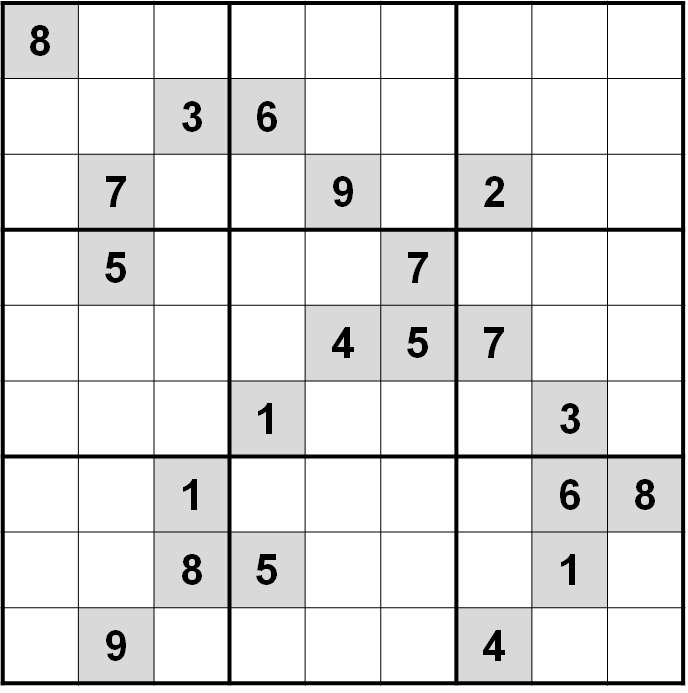

The New York Times publishes daily Sudokus at www.nytimes.com/puzzles/sudoku/. There are three levels: easy, medium and hard. Here is an example of an easy puzzle (left) and a hard puzzle (right).

The easy puzzle has 39 clues. At the start, there are 13 singles. These are cells where there is a candidate that is unique to that row, column, or box. These can be filled in immediately. This will create other singles, until the very end of the puzzle. I can solve such a puzzle in 3-5 minutes.

The hard puzzle has 23 clues. At the start, there are only 2 singles. To solve the rest of the puzzle, one should compare rows, columns and boxes to eliminate candidates. It is very easy to rediscover the other basic strategies: pairs, triples, pointing pairs and box-line reduction. I can solve these puzzles in 20-30 minutes.

It is enough to use the simplest of these strategies combined with depth first search to solve any Sudoku puzzle very quickly.

Very hard puzzles

People however like to challenge themselves. Is it possible to solve a hard Sudoku without any guessing? There are many more complex strategies for solving Sudoku puzzles. For example, constructing chains across multiple rows, columns and boxes to eliminate candidates. Or comparing multiple cells and candidate combinations to eliminate only a single candidate. In general, it is more work for less.

Some puzzles require at least one of these strategies for solving (with no guessing). Andrew Stuart rates them from Tough to Extreme to Diabolical. I don’t solve these puzzles.

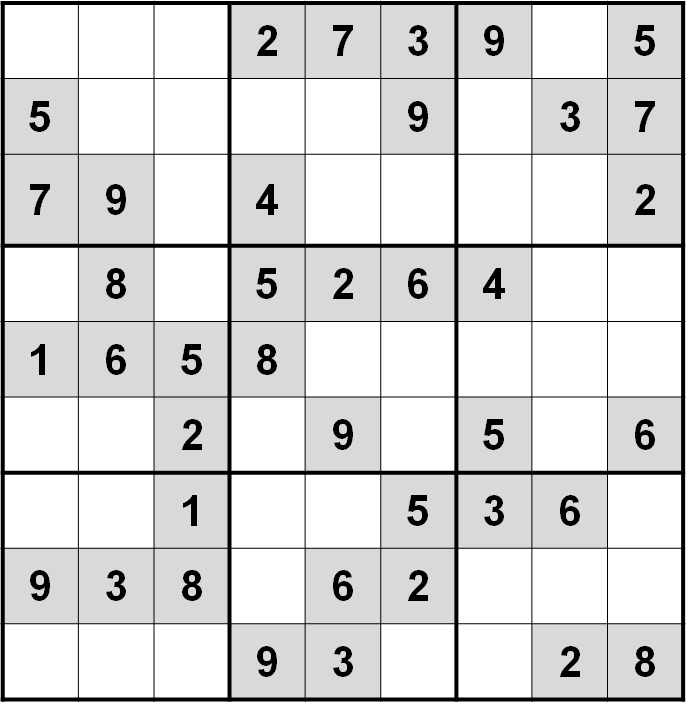

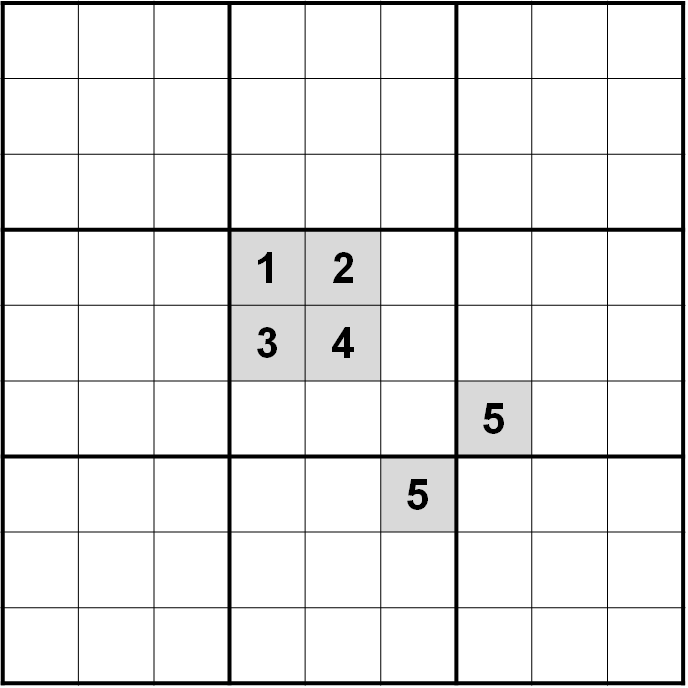

Here is a diabolical puzzle with 26 clues:

This one is particularly nasty. Try put it in Stuart’s solver. It takes multiple steps of small eliminations before the puzzle can be solved. Meanwhile my solver takes only six guesses to solve it.

Ultra-hard puzzles

Ok. So you’ve become a Sudoku master. You abhor guessing. You’ve learnt all the complex techniques. You can create chains across the entire board and swordfishes remind you of your more innocent days. Can you now solve every possible puzzle with logic alone? No guessing? It turns out, no. Stuart himself posts weekly ‘unsolvables’. These puzzles cannot be solved with his logic-only solver. But they are very much solvable with search.

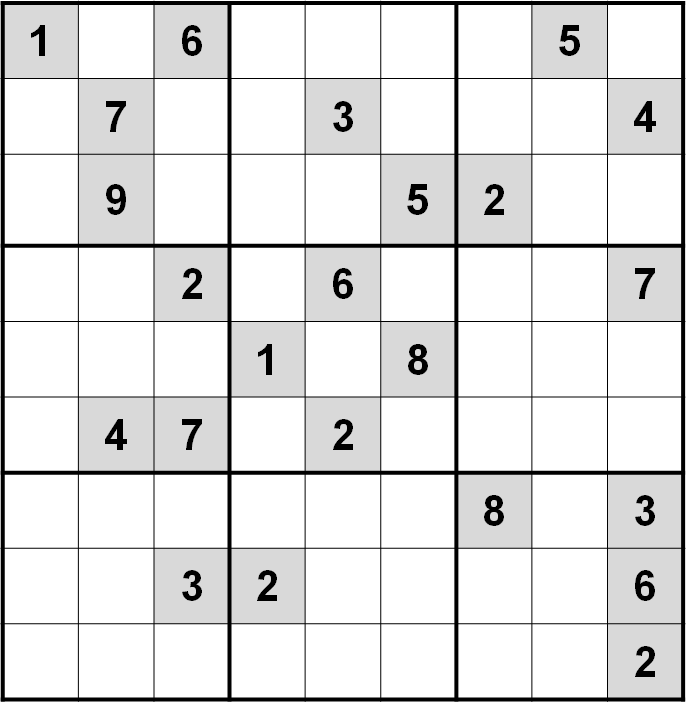

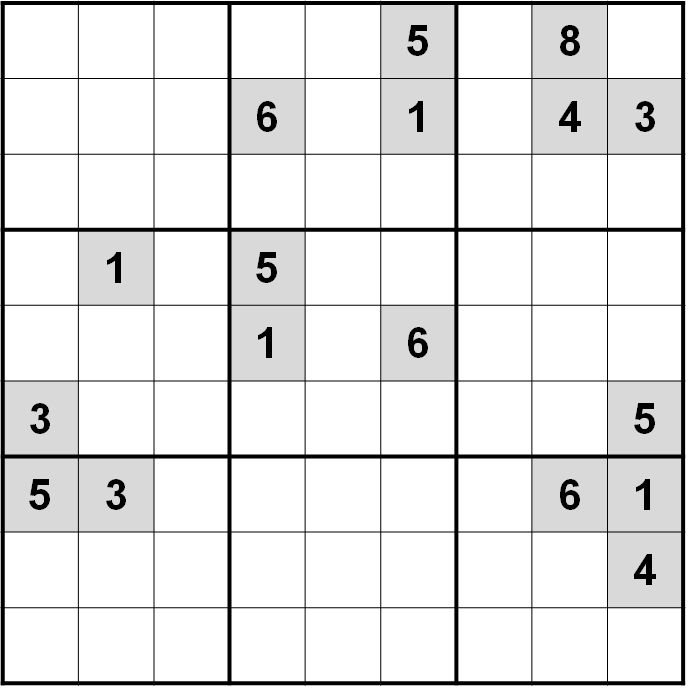

In 2012, this 21-clue puzzle by mathematician Arto Inkala was labelled the hardest Sudoku puzzle in the world:

Is it the hardest? I do not know. But it is certainly a monster. At the very start, one cell has two candidates, and the rest have three. You’re forced to make a guess in the cell with the two candidates. And then at best, another two guesses before you can use any of the techniques in Stuart’s solver. That is a $1$ in $2^3 = 8$ probability of guessing correctly with no wrong guesses. My solver takes 39 guesses to solve this, of which 29 are wrong.1 So in other words, even an amateur like me can solve the hardest Sudoku puzzle in the world by hand, as long as they are willing to do it 40 times.

Impossible puzzles

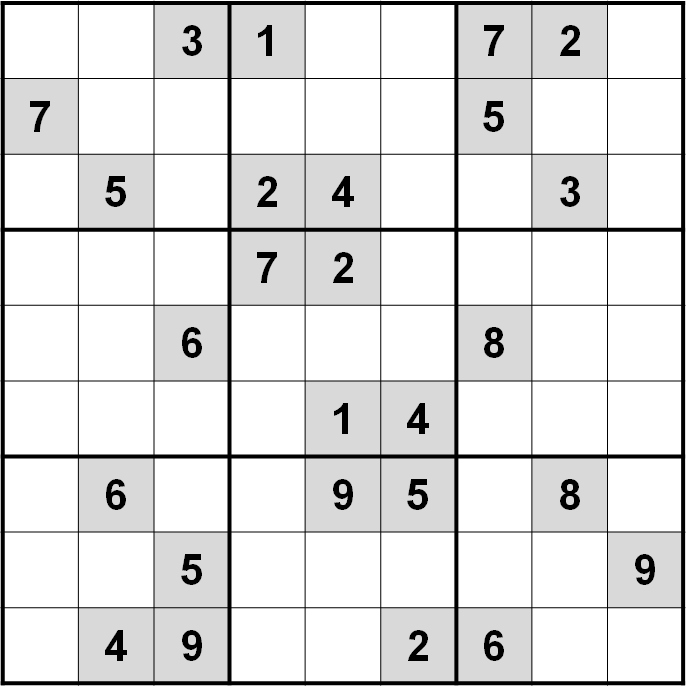

If you search for the term “impossible sudokus” on the internet, you’ll probably find a lot of hard, but certainly solvable, Sudokus. People like to exaggerate the difficulty of these puzzles. There is, however, a very large set of puzzles that are truly impossible. They’re trivially easy to construct. The easiest way to do so, is to play a game of Sudoku and make a mistake 😆 Here are two puzzles which are impossible from the start:

Very amusingly, Norvig passed the puzzle on the right to his solver, and it took almost 24 minutes to conclude that it was impossible. His solver otherwise takes less than a second to solve ultra-hard Sudokus. As an amateur Sudoku player, it took me less than a minute to verify that it was impossible.2

3. Code

General algorithm

To solve even the most challenging of these puzzles, our Sudoku solver only needs to follow three strategies:

- If a square has only one candidate, place that value there.

- If a candidate is unique within a row, box or column, place that value there (hidden singles).

- If neither 1 or 2 is true in the entire grid, make a guess. Backtrack if the Sudoku becomes unsolvable.

In order to check number 2, we have to keep a list of candidates for each block, and update it as values are placed. This adds complexity. We could leave it out - the solver will require more guesses but will still work. However it is easy to find these hidden singles and this step makes the algorithm much faster. So the added complexity is well justified.

Sudoku class

My Sudoku class stores two 9x9 arrays: one is for integers with the final value and another is for candidate values.

I also wrote a few helper functions to extract rows, columns and boxes from the grid.

The __repr__ function overrides the default string for the print function.

from copy import deepcopy

from typing import List, Tuple, Set

SIZE = 9

BOX_SIZE = 3

class Sudoku():

def __init__(self, grid: List):

n = len(grid)

self.grid = grid

self.grid_size = n

# create a grid of viable candidates for each position

candidates = []

for i in range(n):

row = []

for j in range(n):

if grid[i][j] == 0:

row.append(self.find_options(i, j))

else:

row.append(set())

candidates.append(row)

self.candidates = candidates

def __repr__(self) -> str:

repr = ''

for row in self.grid:

repr += str(row) + '\n'

return repr

def get_row(self, r: int) -> List[int]:

return self.grid[r]

def get_col(self, c: int) -> List[int]:

return [row[c] for row in self.grid]

def get_box_inds(self, r: int, c: int) -> List[Tuple[int,int]]:

inds_box = []

i0 = (r // BOX_SIZE) * BOX_SIZE # get first row index

j0 = (c // BOX_SIZE) * BOX_SIZE # get first column index

for i in range(i0, i0 + BOX_SIZE):

for j in range(j0, j0 + BOX_SIZE):

inds_box.append((i, j))

return inds_box

def get_box(self, r: int, c: int) -> List[int]:

box = []

for i, j in self.get_box_inds(r, c):

box.append(self.grid[i][j])

return box

def get_neighbour_blocks(self, r: int, c: int):

inds_row = [(r, j) for j in range(self.grid_size)]

inds_col = [(i, c) for i in range(self.grid_size)]

inds_box = self.get_box_inds(r, c)

inds = [inds_row, inds_col, inds_box]

return inds

def get_neighbour_inds(self, r: int, c: int):

blocks = self.get_neighbour_blocks(r, c)

inds = list(set().union(*blocks))

return indsCandidate functions

These functions are for editing the candidates array. They are also part of the Sudoku class.

Below is the find_options function which is called by __init__.

I’ve chosen to work with the Python set type for working with candidates.

The set functions union (operator |) and difference (operator -) make it easy to find distinct candidates between intersecting rows, columns and boxes.

def find_options(self, r: int, c: int) -> Set:

nums = set(range(1, SIZE + 1))

set_row = set(self.get_row(r))

set_col = set(self.get_col(c))

set_box = set(self.get_box(r, c))

used = set_row | set_col | set_box

valid = nums.difference(used)

return validAs we place values, we’ll need to erase them as candidates in neighbouring blocks. This might then unlock new values elsewhere, so it is useful to do constraint propagation at the same time. While there are many different strategies for constraint propagation, it is sufficient to use only the simplest strategy, hidden singles.

def place_and_erase(self, r: int, c: int, x: int, constraint_prop=True):

""" remove x as a candidate in the grid in this row, column and box"""

# place candidate x

self.grid[r][c] = x

self.candidates[r][c] = set()

# remove candidate x in neighbours

inds = self.get_neighbour_inds(r, c)

erased = [(r, c)] # set of indices for constraint propogration

erased += self.erase([x], inds, [])

# constraint propogation, through every index that was changed

while erased and constraint_prop:

i, j = erased.pop()

for inds in self.get_neighbour_blocks(i, j):

erased += self.set_uniques(inds)

def erase(self, nums: List[int], indices: List[Tuple], keep: List[Tuple]):

""" erase nums as candidates in indices, but not in keep"""

erased = []

for i, j in indices:

edited = False

if ((i, j) in keep):

continue

for x in nums:

if (x in self.candidates[i][j]):

self.candidates[i][j].remove(x)

edited = True

if edited:

erased.append((i,j))

return erased

def count_candidates(self, indices: List[Tuple]):

count = [[] for _ in range(self.n + 1)]

for i, j in indices:

for num in self.candidates[i][j]:

count[num].append((i, j))

return count

def set_uniques(self, indices: List[Tuple]):

uniques = self.get_unique(indices)

erased = []

for inds_unique, num in uniques:

i_u, j_u = inds_unique[0]

self.candidates[i_u][j_u] = set(num)

erased += self.erase(num, indices, inds_unique)

return erased

def get_unique(self, indices: List[Tuple]):

# See documentation at https://www.sudokuwiki.org/Hidden_Candidates

groups = self.count_candidates(indices)

uniques = [] # final set of unique candidates to return

for num, group_inds in enumerate(groups):

if len(group_inds) == 1:

uniques.append((group_inds, [num]))

return uniquesSolver

Here is the full solving algorithm. The code scans through all 9x9 blocks, and tries to place easy candidates following step 1 or 2. It repeats this process until no changes are made. Then either the Sudoku is solved, or we should move onto search through strategy 3. If the latter, the code looks for the block with the smallest number of candidates, and takes a guess there. It then starts with step 1 again. If at any time a block has no candidates, it means a mistake was made, and the code backtracks.

def solve_sudoku(grid, all_solutions=False):

def solve(puzzle, depth=0):

nonlocal calls, depth_max

calls += 1

depth_max = max(depth, depth_max)

solved = False

while not solved:

solved = True

edited = False # if no edits, either done or stuck

for i in range(grid_size):

for j in range(grid_size):

if puzzle.grid[i][j] == 0:

solved = False

options = puzzle.candidates[i][j]

if len(options) == 0:

return False # this call is going nowhere

elif len(options) == 1: # Step 1

puzzle.place_and_erase(i, j, list(options)[0]) # Step 2

edited = True

if not edited: # changed nothing in this round -> either done or stuck

if solved:

solution_set.append(puzzle.grid)

return True

else:

least_candidates = find_least_candidates(puzzle)

i, j = least_candidates[1]

options = puzzle.candidates[i][j]

for guess in options: # step 3. backtracking check point:

puzzle_next = deepcopy(puzzle)

puzzle_next.place_and_erase(i, j, guess)

solved = solve(puzzle_next, depth=depth+1)

if solved and not all_solutions:

break # return 1 solution

return solved

return solved

calls, depth_max = 0, 0

solution_set = []

puzzle = Sudoku(grid)

grid_size = puzzle.grid_size

solved = solve(puzzle, depth=0)

info = {'calls': calls,

'max depth': depth_max,

'nsolutions': len(solution_set),

}

return solution_set, solved, info

def find_least_candidates(puzzle: Sudoku):

n = puzzle.grid_size

least_candidates = (n + 1, (0, 0))

for i in range(n):

for j in range(n):

if len(puzzle.candidates[i][j])> 0:

options = puzzle.candidates[i][j]

least_candidates = min((len(options), (i, j)), least_candidates)

return least_candidatesAuxiliary functions

Puzzles can be represented in serial format by concatenating rows instead of stacking them. Then instead of storing it as array, it could be stored as a string. This makes it easy to store and retrieve many different puzzles. For example, here is the hard Inkala puzzle:

800000000003600000070090200050007000000045700000100030001000068008500010090000400

Or with ‘.’ instead of ‘0’ for blanks:

8……….36……7..9.2…5…7…….457…..1…3…1….68..85…1..9….4..

The following functions convert between these serial formats and a grid.

def flatten(grid) -> List[int]:

arr = []

for row in grid:

arr.extend(row)

return arr

def unflatten(arr: List[int], n=9) -> List[List[int]]:

grid = []

for i in range(0, len(arr), n):

grid.append(arr[i:i+n])

return grid

def arr2str(arr: List[int]) -> str:

string = ''

for digit in arr:

string += str(digit)

return string

def str2arr(string: str) -> List[int]:

arr =[]

end = string.find('-')

end = len(string) if end == -1 else end

for c in string[0:end]:

if c=='.':

arr.append(0)

else:

arr.append(int(c))

return arr

def grid2str(grid: List[List[int]]) -> str:

return arr2str(flatten(grid))

def str2grid(string: str) -> List[List[int]]:

return unflatten(str2arr(string))4. Analysis

This code takes 0.15s and 39 calls to solve to solve the Inkala puzzle. The maximum call depth is 10.

For Norvig’s 95 hard puzzles, the code takes a total of 11.69s, with an average time of 0.12s per puzzle. The average number of calls is 93.0, while the maximum number of calls is 588. This is slower than Norvig’s code. I am unsure if this is because of the algorithm, the implementation or because of my hardware. For Norvig’s 11 hardest puzzles, the total time is 0.24s, with an average of 0.023s per puzzle. The average number of calls is 15.6 with a maximum number calls of 55.

Out of curiosity, I added more advanced strategies: pairs, triples and pointing pairs. For the 95 puzzles, this reduces the total solving time to 3.52s and it reduces the average time to 0.037s. The average number of calls is just 11.6 and the maximum number of calls is 74. For the 11 hardest puzzles the solving time is slightly slower at 0.029s per puzzle. The average number of calls decreased to 11.6, while the maximum number of calls increased to 74. This shows there are only marginal gains for a lot more effort. Also, they make no difference to the solving path for the Inkala puzzle.

The full code with the advanced strategies can be viewed at my GitHub repository at: https://github.com/LiorSinai/SudokuSolver-Python.

There are also additional functions which are not described here. For example, check_possible which will flag impossible puzzles like the ones shown earlier.

5. Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed reading about my Sudoku solver. In some ways, being able to solve every Sudoku puzzle in under a second trivialises the appeal of Sudoku. But I still like to solve mildly challenging Sudokus by hand. It helps me to take my mind off things and relax.

-

This is a high ratio of 3:1 for wrong:correct guesses. It arises because after a wrong guess is taken all the guesses after that are also wrong until the algorithm backtracks. If we only count the first wrong guess, then the ratio is 4:6. ↩

-

Look at the middle column. The three sets of 1, 5 and 6 require that the three numbers 1, 5 and 6 fit in the two blocks of H5 and J5. Impossible. ↩