This post details a backtracking algorithm for solving scramble square puzzles. This is a deceptively simple looking puzzle, with only 9 pieces, but it can be very challenging to solve, with over 23.8 billion possible arrangements.

Scramble Squares

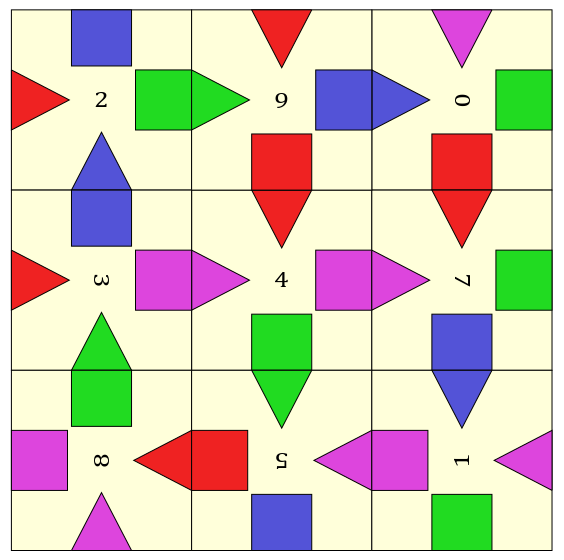

When I was a child, I used to spend many hours trying to solve a scramble square puzzle. An example is shown above. The puzzle consists of nine square pieces and four images spread across the squares. On each side on each square is half of one of the four images. For example the top half of an elephant. Some of the other pieces have the corresponding half, like the bottom half of the elephant. The aim to is arrange the pieces in a 3x3 grid such that all inner images are aligned - all halves are matched. This is actually very difficult, and I was not able solve it.

Much later, when I was in university, I returned to this puzzle. I wondered if there was a procedural method to solve it. Such methods exist for Rubik’s cubes. I was not able to find any, but I did find a depth first search backtracking algorithm for it described in this paper. This algorithm is rather painful to do by hand, but easy to implement with a computer. I wrote up the algorithm in Python, and within a second, I found the two solutions for my puzzle. So much for hours of frustration when I was younger!

The rest of this post will describe this algorithm in detail.

The algorithm

The search space for this puzzle is surprisingly large. There are $9!$ permutations for placing each puzzle piece, and each piece has 4 orientations, except for the middle piece (because rotating this piece just rotates the entire puzzle). This gives $4^8 9! \approx 23.8$ billion arrangements of the puzzle. Therefore, just trying every puzzle arrangement is too slow.

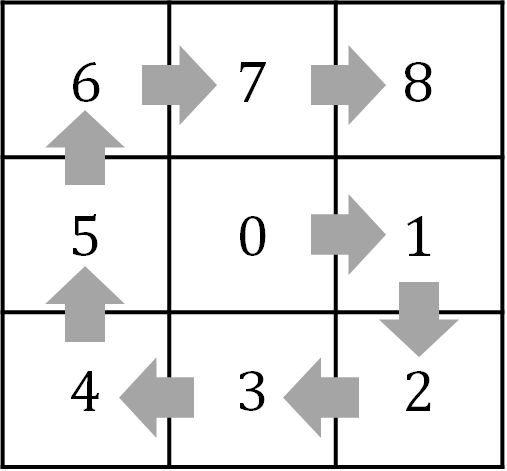

The backtracking algorithm is more efficient. In this algorithm, each piece is placed one at a time in the order shown above. Then either the piece fits, and we move onto the next position, or it does not and we try a new piece. If we run out of pieces, we backtrack to the last position where a piece was placed, and try a new piece. If we reach position k=8 and the last piece fits successfully, a solution is registered. Then we backtrack again to find other solutions.

This algorithm very effectively cuts down the search space. If a piece does not fit in the kth position, then all arrangements with the piece in that position are skipped. So if for example, a piece does not fit in position k=1, then all $4(4^7 7!)$ arrangements with the piece in this position are skipped. That’s 1.4% of the total search space.

The Python code

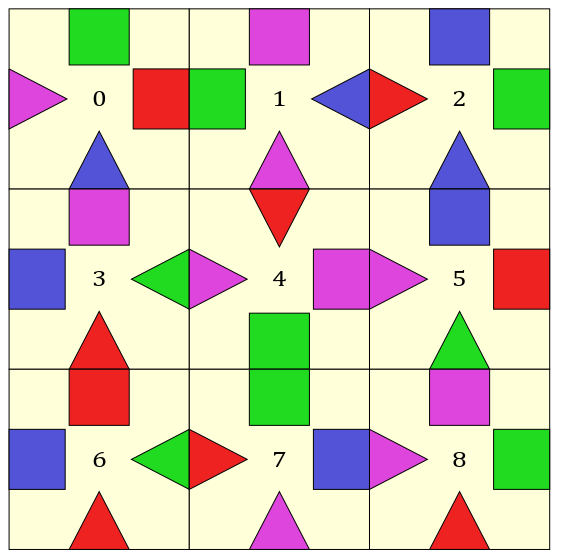

The Serengeti puzzle I posted above has no solution1. So instead I’ll use a mock-up of a puzzle I had as a child. This is shown above. The goal here is to match triangles with blocks of the same colour. I’ve labelled each piece from 0 to 8. Each piece is encoded as an array using the following rules:

- Colours are mapped to a number: blue → 1, green → 2, red → 3 and purple → 4.

- Triangles are positive and blocks are negative.

- Sides are labelled starting from the top and going clockwise.

For example, piece 0 is encoded as [-2, -3, +1, +4].

The rest of the pieces look like:

blue, green, red, purple = 1, 2, 3, 4

pieces = [

[-green,-red,+blue,+purple],

[-purple,+blue,+purple,-green],

[-blue,-green,+blue,+red],

[-purple,+green,+red,-blue],

[+red,-purple,-green,+purple],

[-blue,-red,+green,+purple],

[-red,+green,+red,-blue],

[-green,-blue,+purple,+red],

[-purple,-green,+red,+purple]

]The state of the puzzle can be summarised in two variables: order, a list of the order of placements of pieces, and rot, the current rotation applied to each piece.

A rotation is encoded as a number from 0 to 3.

I created a simple class to store this state. I’ve also made a nice representation for the print function, and two functions that I’ll leave abstract for now.

class ScrambleSquare():

def __init__(self, pieces: List[int]):

self.pieces = pieces

self.order = [-1, -1, -1, -1, -1, -1, -1, -1, -1]

self.rot = [0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

def __repr__(self):

repr = ''

order = self.order

repr += ' '.join(map(str, [order[6], order[7], order[8]])) + '\n'

repr += ' '.join(map(str, [order[5], order[0], order[1]])) + '\n'

repr += ' '.join(map(str, [order[4], order[3], order[2]]))

return repr

def fit_2pieces(self, piece1: List[int], rot1: int, side1: int,

piece2: List[int], rot2: int, side2: int) -> bool:

pass

def fit_position(self, k: int, used_k: int, rot_k: int) -> bool:

passI can now present the algorithm in full. I will go into the detail of the abstract functions afterwards:

def solveScramble(pieces: List[int]) -> None:

def solve(k: int, puzzle, stack: List[int]):

calls[k] += 1

if k == SIZE: # terminate recursion

print('Solution found!!')

print(puzzle)

for idx in range(len(stack)): #select a new piece that hasn't been used

new = stack[idx]

for r in range(NUM_ORIENTATIONS): #try different orientations

if puzzle.fit_position(k, new, r): #backtracking checkpoint

puzzle_next = copy(puzzle)

puzzle_next.order[k] = new

puzzle_next.rot[k] = r

stack_next = stack[:idx] + stack[idx + 1:] # remove stack[idx]

solve(k + 1, puzzle_next, stack_next)

if k == 0:

break #don't rotate the first piece

calls = [0] * (SIZE + 1)

stack = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

puzzle = ScrambleSquare(pieces)

solve(0, puzzle, stack) # initiate recursionI’ve written the algorithm as a recursive function, so that Python’s memory stack can keep track of different puzzle states for us.

This could also be done in for loop, but then the backtracking has to be explicitly implemented.

Note: the constants are NUM_ORIENTATIONS=4 and SIZE=9. The calls variable is useful for analysing the results.

Now let’s elaborate the abstract functions2. The fit_2pieces() function is simple.

Two pieces “fit” if the sum of the touching sides is 0. So it is written as:

def fit_2pieces(self, piece1: List[int], rot1: int, side1: int,

piece2: List[int], rot2: int, side2: int) -> bool:

return piece1[side1 - rot1] + piece2[side2 - rot2] == 0Pieces are “rotated” 90° counter-clockwise by subtracting a value from the index. The indexing behaviour of Python conveniently wraps around with negative numbers,

so something like piece1[0 - 1] is evaluated as piece1[-1]=piece1[3].

The fit_position() function is not as straightforward. Each piece needs to fit with the previous piece, but the sides which are compared are different at each position.

Also, at positions 3, 5, 7 and 8, two sides on the piece need to be checked.

I found it was easiest to hardcode all this. This is what it looks like, after some refactoring:

def fit_position(self, k: int, used_k: int, rot_k: int) -> bool:

if k == 0:

fits = True

else: #Each piece must fit with the previous piece:

piece_k = self.pieces[used_k]

side_k = [1, 3, 0, 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3][k]

piece_j = self.pieces[self.order[k - 1]]

rot_j = self.rot[k - 1]

side_j = [0, 1, 2, 3][side_k - 2] #picks the opposite side

fits = self.fit_2pieces(piece_k, rot_k, side_k, piece_j, rot_j, side_j)

#Extra fitting criteria for particular positions:

if k in [3, 5, 7, 8]:

pieces, order, rot = self.pieces, self.order, self.rot

if k == 3:

side_k = 0

piece_other, rot_other, side_other = pieces[order[0]], rot[0], 2

elif k == 5:

side_k = 1

piece_other, rot_other, side_other = pieces[order[0]], rot[0], 3

elif k == 7:

side_k = 2

piece_other, rot_other, side_other = pieces[order[0]], rot[0], 0

elif k == 8:

side_k = 2

piece_other, rot_other, side_other = pieces[order[1]], rot[1], 0

fits = fits and self.fit_2pieces(piece_k, rot_k, side_k, piece_other, rot_other, side_other)

return fits Results

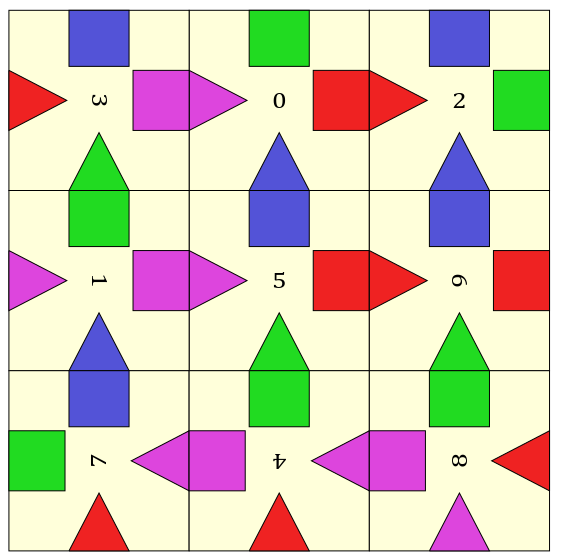

This code retrieves the following solutions in 0.07 seconds:

These are the only two solutions for this puzzle.

In total, it calls solve 588 times. The final calls list looks like:

[1, 9, 43, 165, 70, 151, 68, 60, 19, 2].

So, 19 times the code placed 8 pieces, but only 2 of those times was it able to progress to a solution.

Conclusion

This is tough puzzle to give to someone. Certainly, as an engineer and as a programmer, I would approach this problem with an algorithmic way of mind. However, when I was younger, I was not thinking along those lines at all. I wonder though, if with guidance, it is worthwhile showing this to a young student. It would teach them the value of algorithms. They do not need to know how to code - it is possible to implement this algorithm by hand. Although it took me 1.5 hours, I was able to do this recently. Part of the reason it took so long was because I was trying to be clever and skip steps. But once I followed the simple rules with the physical stack in my hand, I got into a rhythm and it went quickly. In any case, it is definitely a worthwhile coding exercise in backtracking and recursion.

-

At first, I thought this was a mistake. However after failing to find solutions for several other puzzles on that website, I think this was deliberate. This is a crude form of copyright protection - it prevents you from copying the puzzles (from this website at least). ↩

-

The original paper does not describe the abstract functions at all. ↩