Calculating probabilities for matching games like Dobble.

Update 24 April 2023: Corrected calculation for randomly evenly distributed probabilities. The original assumed P(card from different bag) = P(different bag). These quantities are however only approximately equal.

Table of Contents

Dobble

Dobble is a card game where there are 57 cards and each card has 8 symbols on them. Quite remarkably, each card only shares a single symbol with any other given card. In the image above the top two only share the cheese and the bottom two only the carrot. Can you find the other four pairs (two left, two right, two on two diagonals)?

I was recently challenged to answer how this is possible. I immediately thought to probability but that led me down the wrong path - the answer lies in finite projective plane geometry. There are many good articles on this on the internet. As a starting point I recommend reading the Wikipedia articles on Dobble and projective planes and their references.

However I was still curious about the probabilistic approach. Dobble guarantees a single collision at 100% probability. How much better is this than random?

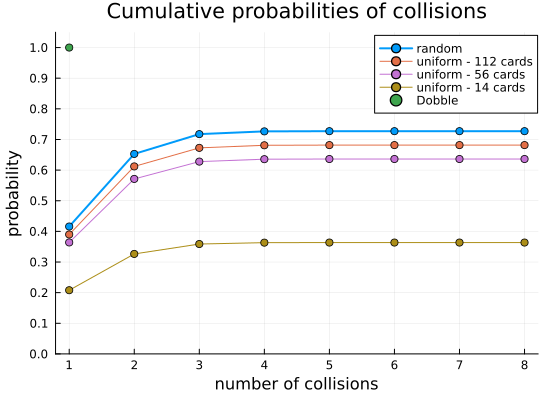

The answer turns out to be about approximately 30%. This is because random cards give a 72% chance of a collision. There is about 41.6% of any two cards sharing a match. To this we can add another 23.7% chance for sharing two symbols and 6.5% chance for sharing three symbols and so on until all symbols match.

The blue line in the graph above shows these cumulative probabilities. The other lines represent more carefully constructed but still random cards. The green dot represents Dobble cards. They are certainly an outlier - only one collision with 100% probability.

The next two sections detail how this graph was constructed. The main mathematical prerequisite here is knowledge of the binomial coefficient $\binom{n}{k}$, read as “n choose k”. The last section details an algorithm for generating Dobble-like cards. It is a visual algorithm.

Random cards

Dobble has $S=57$ symbols spread across $N=55$ cards with $s=8$ symbols per card. These cards are very specially constructed. But what if we just make them randomly?

Imagine having a bag with the $S$ symbols inside it. Then for every card you randomly take $s$ symbols out of the bag, draw them on the card and put them back. This is done for $N$ cards. We can simulate this with the following algorithm:1

Random sampling

Initialise $C \leftarrow \{\}$

for $i$ in $1:N$

$\quad$ $c \leftarrow$ sampleWithoutReplacement($S$, $s$)

$\quad$ $C$.insert($c$)

What is the probability there will be collisions between any two cards? That is, what is the probability at least one symbol will match on each card?

We’ll start with just one matching pair of symbols with $S=57$ and $s=8$. We have $\binom{8}{1} =8$ ways to choose which symbol matches on the first card. Then we have $7$ symbols to choose from the remaining $49$ symbols for the second card. This is out of a total of $\binom{57}{8}\approx1.65\times10^9$ ways to make a single card:

\[\begin{align} P(X=1) &= \frac{8 {\binom{49}{7}}}{\binom{57}{8}} \\ &= 0.4159 \end{align}\]In general for $k$ matching symbols, we have $\binom{s}{k}$ ways to choose which of the $s$ symbols on the first card match and then ${s-k}$ symbols to choose from the remaining $S-s$ symbols for the second card. There are ${\binom{S}{s}}$ ways in total to make a single card:

\[P(X=k) = \frac{\binom{s}{k}\binom{S-s}{s-k}}{\binom{S}{s}}\]The probability that there is no collision can be found by summing up these probabilities and subtracting it from one. This is also equivalent to making the second card by drawing $s$ symbols from the remaining $S-s$ symbols not on the first card.

\[P(X=0) = 1-\sum_{k=1}^{k=s} P(X=k) = \frac{\binom{S-s}{s}}{\binom{S}{s}}\]Therefore for the random Dobble cards:

\[\begin{align} P(X>0) &= \sum_{k=1}^{k=s} P(X=k) \\ &= 1 - P(X=0) \\ &= 1 - \frac{\binom{49}{8}}{\binom{57}{8}} \\ &= 0.7271 \end{align}\]So if the cards are made randomly there is still a 72.7% chance of a match. This is more than two thirds of the time. Of those matches about 57% will involve only one symbol and another 33% will involve two symbols. The remaining 10% of matches are spread across the more rare three to eight symbol matches.

Uniformly random cards

In Dobble each symbol appears seven or eight times on all cards. If the manufacturers had used 57 cards instead of 55 then each symbol would appear exactly eight times. For the random cards this distribution is more varied. A single symbol is spread across the cards with a binomial distribution with probability $\frac{1}{S}$. The frequency for any given symbol therefore has a mean $\mu=\frac{Ns}{S}$ and standard deviation $\sigma=\frac{1}{S}\sqrt{Ns(S-1)}$. For $N=55$, $S=57$ and $s=8$, $\mu=7.72$ and $\sigma=2.75$.

My next thought was, what if we create cards randomly but distribute the symbols so that each symbol only appears on seven or eight cards? Imagine taking eight bags and filling each with 57 symbols. Then take out eight symbols at a time from each bag without replacement. You’ll be able to make seven unique cards from each bag with one symbol spare. All in all you’ll have 7 cards/bag × 8 bags =56 cards.

The following is an algorithm for doing this in code (assuming 0-based indices):2

Evenly distributed sampling

Initialise $C \leftarrow \{\}$, symbols$\leftarrow\{1,2,...,S\}$

partitions $\leftarrow \lfloor{S/s\rfloor}$

for $j$ in 1:$b$

$\quad$ symbols $\leftarrow$ shuffle(symbols)

$\quad$ for $i$ in 1:partitions

$\qquad$ idx $\leftarrow (i-1)s$

$\qquad$ $c \leftarrow$ {symbolsidx ,..., symbolsidx+$s$-1}

$\qquad$ $C$.insert($c$)

The probability that there are collisions with these cards is very similar to the random case. Except now we have to take into account which bag the cards were generated from. If they were generated from the same bag then there will not be a match. Else apply the same formula as before.

The probability that the card is from a different bag is

\[\begin{align} P(\text{card from different bag}) &= \frac{N-p}{N-1} \\ &= \frac{(bp)-p}{(bp)-1} \\ &= \frac{b-1}{b-\frac{1}{p}} \\ &\approx \frac{b-1}{b} = P(\text{different bag}) \end{align}\]Where $b$ is the number of bags and $p$ is the number of partitions per bag. Equivalently, $p$ is the number of cards per bag. We minus 1 from the denominator to exclude the first card.

The probability of a collision is then:

\[\begin{align} P(Y=k | k >0) &= P(\text{card from different bag}) \cap P(X=k) \\ &= \frac{b-1}{b-\frac{1}{p}}\frac{\binom{s}{k}\binom{S-s}{s-k}}{\binom{S}{s}} \end{align}\]For example for $k=1$, $b=8$ and $p=7$, $P(Y=1)=\frac{7}{8-\frac{1}{7}}P(X=1)=37.1\%$. The probability of collisions will always be lower than the random case but will converge towards it as more bags are used.

The probability of no collisions is the probability that they are from the same bag plus the random collision probability if they are from different bags:

\[\begin{align} P(Y=0) &= P(\text{card from same bag}) \cup [P(\text{card from different bag}) P(X=0)] \\ &= \frac{1-\frac{1}{p}}{b-\frac{1}{p}} + \frac{b-1}{b-\frac{1}{p}}\frac{\binom{S-s}{s}}{\binom{S}{s}} \end{align}\]For $b=8$ and $p=7$ there is a 35.2% chance of a no collision or 64.8% chance of at least one collision.

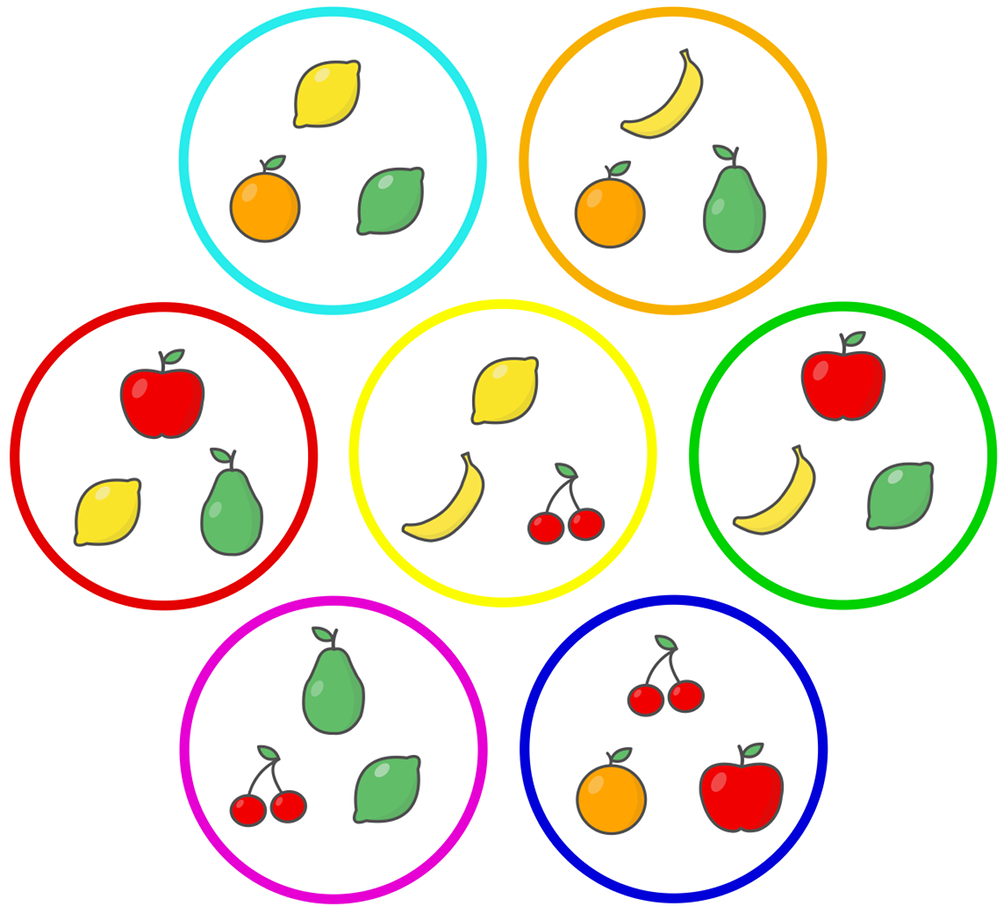

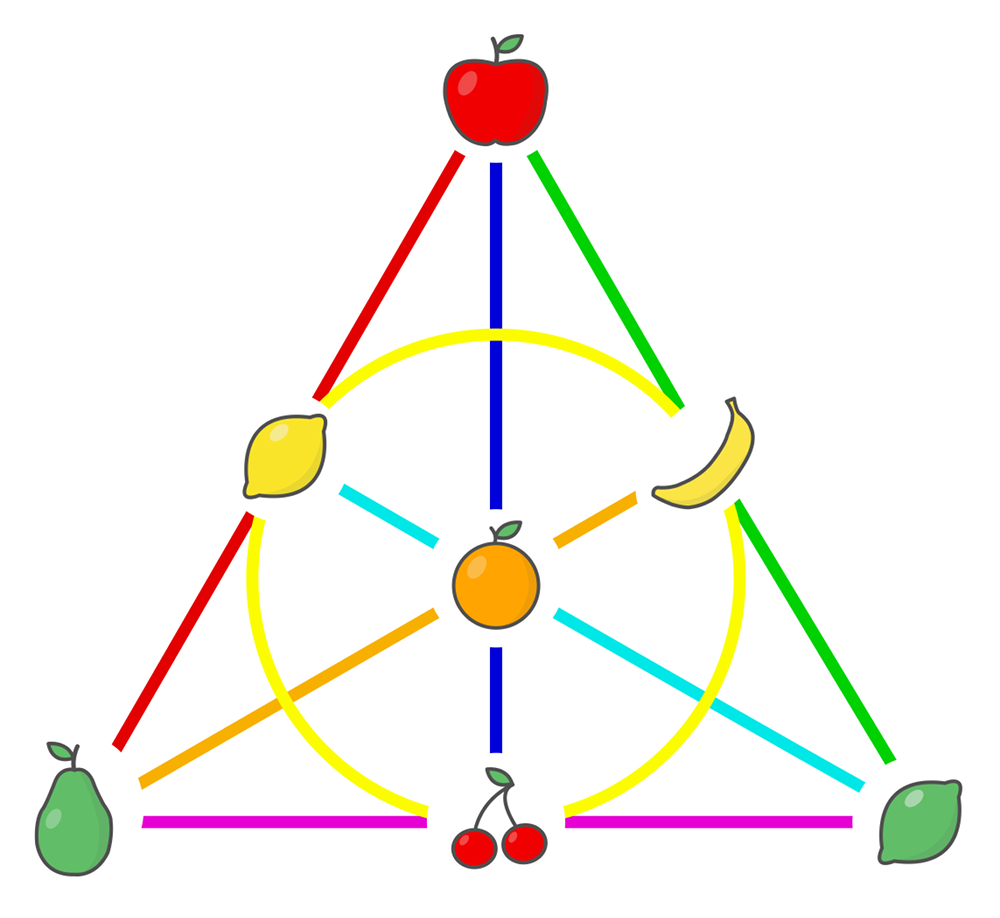

Generating finite projective planes

Dobble cards are generated via a finite projective plane. Each card can be represented as a line and each symbol a dot on this line. The lines can be arranged such that each line only intersects each other line at one dot. The Fano plane is the result for the case of $s=3$ as illustrated in the image below.

A 3 symbol Dobble game (left) and the corresponding Fano plane (right) from puzzlewocky.com/games/the-math-of-spot-it/.

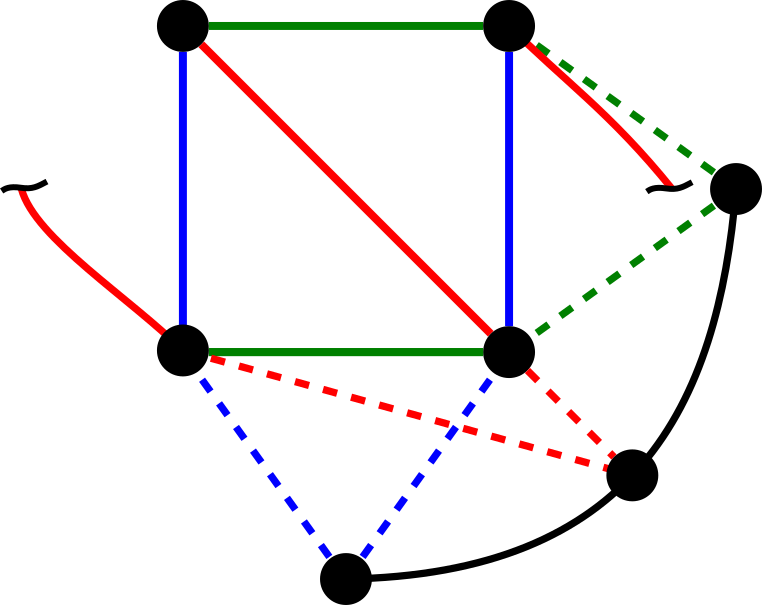

To generate the real Dobble game we could try draw all 57 lines such that they also each intersect each other at one point. That will get messy very quickly. Thankfully there is a better technique for drawing finite projective planes. Here is the same $s=3$ geometry as above but rearranged into a 2×2 grid and 3 points on a curve:

The algorithm is as follows:

- Create an $n\times n$ grid of points.

- Draw $n$ sets of parallel lines through the grid where the slope of the lines varies from (1,1) to (1,$n$). If the line goes off the grid, wrap it around. That is, $j \leftarrow (j +m_j)\mod n$ where $m$ is the slope and the indices are zero based.

- Add a set of parallel lines for the rows where slope=(0, 1).

- Add $n+1$ vanishing points at infinity where these parallel lines “intersect”.

- Make one final card from a line through the vanishing points.

Note this only works for finite planes of order $n=s-1$ where $n$ is prime.

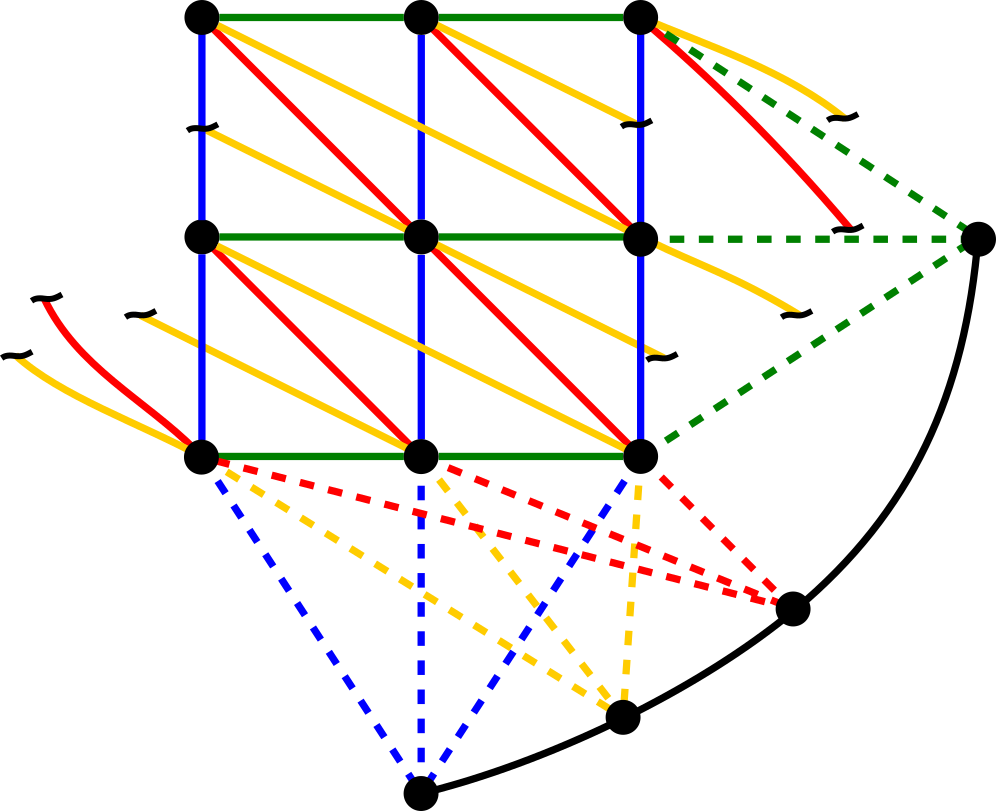

Each plane will have $n^2$ symbols on the grid and $n+1$ symbols on the vanishing points for a total of $n^2+n+1$ unique symbols. It will have the same number of lines. In this framework Dobble is an order 7 plane with 8 symbols on each card, 57 unique symbols and 57 possible cards.

Here is an order 3 plane with 13 symbols:

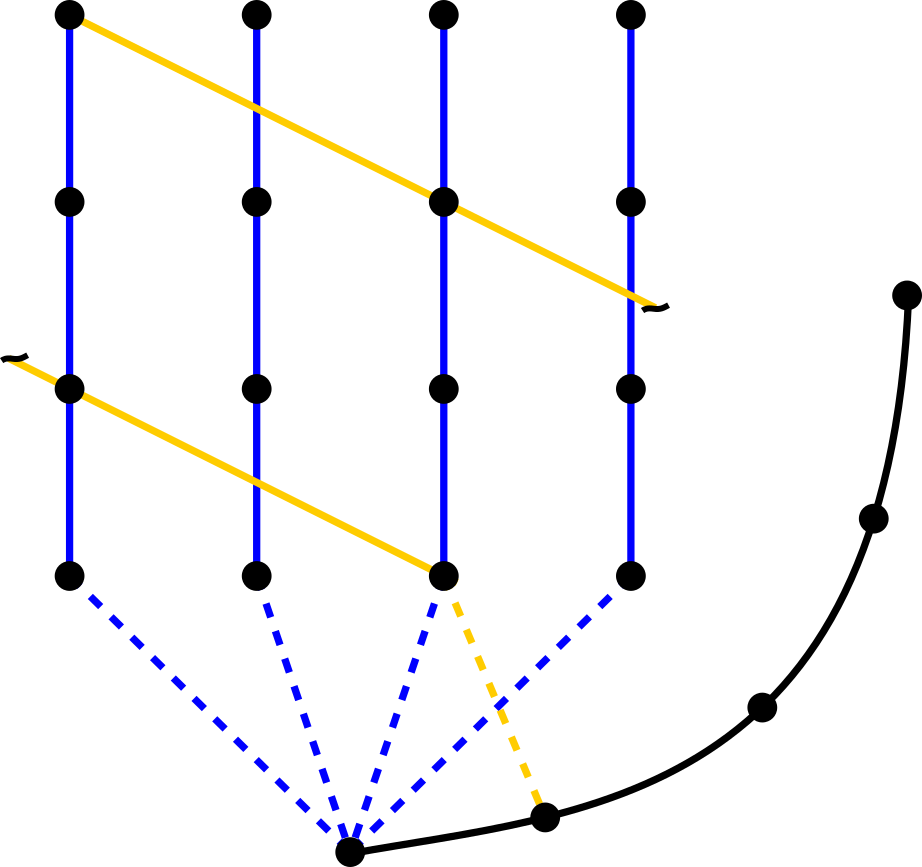

For order 4 this method will fail. Four is not prime so the wrapping around will cause some points to intersect more than once, resulting in more than one symbol matching on some cards. The example below shows a slope (1, 2) line intersecting with the first column twice:

Final thoughts

It is actually possible to make an order 4 finite projective plane but with other techniques. According to Wikipedia, it is known that it is always possible for $n$ that is a power of a prime and $4=2^2$. An unanswered question is when is it not possible? A proof exists for the first failure case of $n=6$ and it has been computationally verified that no solution exists for $n=10$. It is thought that $n=12$ fails as well but this has not been confirmed. To say that it another way, no one knows for sure that it is impossible to make a Dobble game with 13 symbols on each card.

This might sound surprising but consider that such a game would have $12^2+12+1=157$ symbols. Then there are $\binom{157}{13}=3.4\times 10^{18}$ ways to make each card. That is a truly massive number. To put it in perspective, it is more seconds than there are in 100 billion years.

Even with this simple game we have come across a question that is at the frontier of mathematics.