Exact probabilities for counting the chance of collisions with distinct objects, using the birthday problem as a working example.

Introduction

This follows from my previous blog post on Intuitive explanations for non-intuitive problems: the Birthday Problem. Please see that post for a heuristic understanding of the problem. It assumed independence of sharing birthdays. This post makes no such assumption, so the mathematics is more advanced. A background in counting methods with combinations and permutations is required.

Table of contents

- Probability of at least 1 collision

- Probability of k collisions

- Probability of groups of collisions

- Probability of collisions when drawing from a distribution

Probability of at least 1 collision

In the previous post I assumed independence between sharing birthdays. But sharing is dependent. If person A and person B share a birthday, then sharing a birthday with person B depends on sharing a birthday with person A. Counting methods can account for this dependence.

As in my the previous post, it is easiest to work backwards. First find the probability that no people share a birthday and then subtract this from 1. For $n$ people, we can imagine shuffling $k=n$ unique birthdays in $k$ slots yet for each one we have a choice of 365 birthdays:

\[\begin{align} P(x \geq 1 | n=k) &= 1 - \frac{365}{365}\frac{364}{365}...\frac{365-k+1}{365}\\ &= 1 - \frac{^{365}P_{k}}{365^k} \end{align}\]For 23 people this gives a probability of 0.5073.

Composition of probabilities for shared birthdays between 23 people

The next question is, how is this probability composed? The next sections will show that of the collisions that happen, 72% will be just one pair, and 22% two pairs. (Unselect “none” in the pie chart above to see this.)

Probability of $k$ collisions

What is the chance of $k$ out of $n$ people sharing a birthday? Or more concretely, only 2 people sharing in a group of 23?

There are ${23 \choose 2}=253$ ways that two people can be chosen. Separately we can imagine filling 22 slots with distinct birthdays. (Not 23 because one is shared.) There are $^{365}P_{22}$ ways of filling these slots. The total probability is then:

\[\begin{align} P(x=2 | n=23) &= {23 \choose 2} \frac{^{365}P_{22}}{365^{23}} \\ &= 0.3634 \end{align}\]Similarly for three people sharing a birthday:

\[\begin{align} P(x=3 | n=23) &= {23 \choose 3} \frac{^{365}P_{21}}{365^{23}} \\ &= 0.0074 \end{align}\]This is much more unlikely.

Probability of groups of collisions

There can also be two pairs sharing birthdays. Or three pairs. Or two pairs and a triplet and a quintuplet.

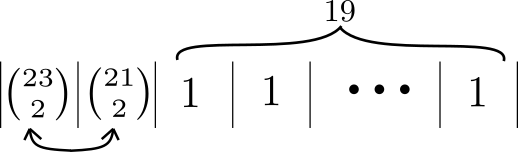

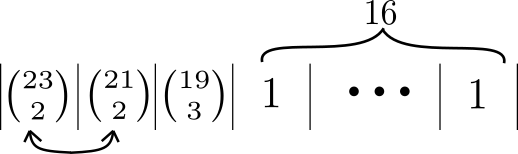

First let’s take the case of two pairs amongst 23 people in total. We first choose 2 to be part of the first pair ($\binom{23}{2}$), then 2 of the remaining 21 to be part of the second pair ($\binom{21}{2}$). We can shuffle the birthdays between 21 unique slots ($^{365}P_{21}$). The first two slots can be shuffled without changing the arrangement because they both have identical looking pairs ($2!$). The probability is then:

Now let’s add a set of three to these pairs:

This is much more unlikely.

To get the probability of at least 2 people sharing, instead of using the method in the first section, we can go through all ways of partitioning $k$ people. This is known as the integer partition problem. In practice, I find it is accurate enough to only consider up to 3 or 4 people sharing a birthday, because the other scenarios are so unlikely. However that other method is much simpler.

Probability of collisions when drawing from a distribution

A rather subtle but important assumption made in the previous sections is that we are drawing people from a large population. This assumption breaks down when drawing from a small sample. For example, Facebook friends. We can only draw as many pairs, triples and sets in general as exist.

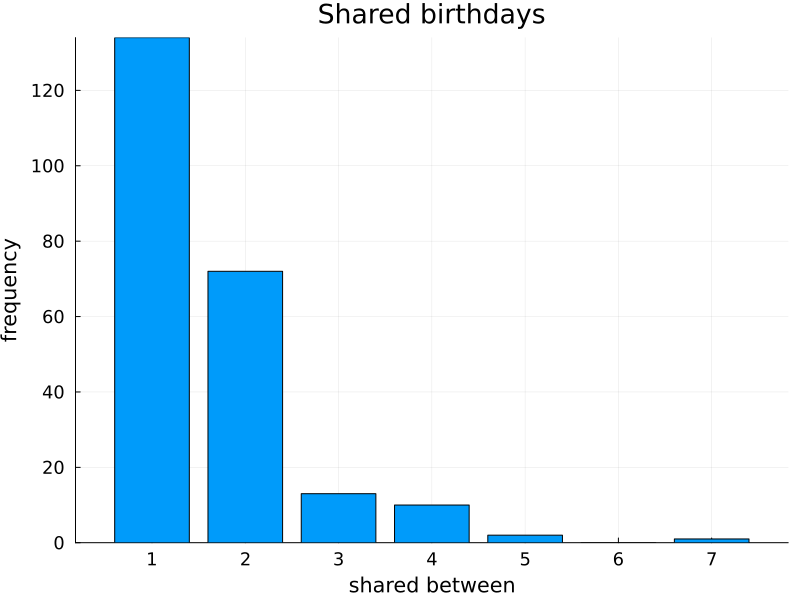

Here is the distribution of shared birthdays between my Facebook friends:

| Shared between | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Frequency | 134 | 72 | 13 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

Plotted as a bar graph:

So in my group of friends there is a day where seven people share a birthday but none where six do. So I cannot include this probability in the calculation, which the calculation in the previous section does.

The probability of drawing from a distribution is a tricky problem. One notable application is calculating probabilities of hands in poker.

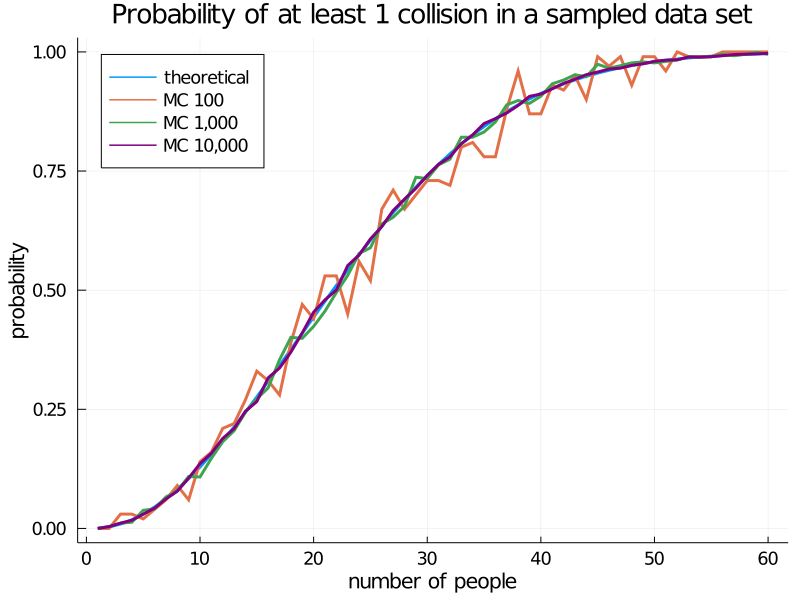

It is simpler and quicker to run Monte Carlo simulations, as I did in my previous post. Here is a comparison of running 1,000 and 10,000 trials per point compared to the true curve:

The Monte Carlo simulations hold up well. The MC 10,000 curve is almost indistinguishable from the theoretical curve.

But how does one calculate the theoretical curve? Let’s start with simpler, very specific problems.

We start with 30 friends of which none share birthdays and further, they do not share birthdays with people outside of group.

- There are $\binom{374}{30}$ ways in total to choose 30 people.

- All the 30 most come from the set of $n_1=132$ singletons: $\binom{132}{30}$.

- The distribution is characterised by $D$.

Next we have another group of 30 friends of which none share birthdays, but now one shares a birthday with one person outside of the group:

- There are $\binom{374}{30}$ ways in total to choose 30 people.

- From the $n_2=72$ pairs, we need to select one from $\binom{2}{1}=2$ possible people from $\binom{72}{1}=72$ possible pairs.

- The remaining $29$ all come from the set of $n_1=132$ singletons: $\binom{132}{29}$.

Let’s complicate this more. We are still selecting 30 friends of which none share birthdays, but now 10 share birthdays with one other friend (not in the 30), and 2 share with two other friends each, and 1 is one of the 7 that share a birthday on the same day:

- There are $\binom{374}{30}$ ways in total to choose 30 people.

- From the $n_2=72$ pairs, I want to select 10 from $\binom{72}{10}$ combinations of pairs, 1 of 2 from each pair $\binom{2}{1}^{10}$.

- From the $n_3=13$ triples, I want to select 2 from $\binom{13}{2}$ combinations of triples, 1 of 3 from each triple $\binom{3}{1}^{2}$.

- From the $n_7=1$ sevens, I want to select 1 person of 7 $\binom{7}{1}$.

- The remaining $17$ all come from the set of $n_1=132$ singletons: $\binom{132}{17}$.

Hence the total probability is: \(\begin{align} P&(x=(1\times 17, 2\times 10, 3\times 2, 7\times 1)|D,n=30) \\ &= \binom{132}{17} \left[ \binom{72}{10} \binom{2}{1}^{10} \right] \left[ \binom{13}{2} \binom{3}{1}^2 \right] \left[ \binom{1}{1} \binom{7}{1} \right] \div \binom{374}{30} \\ &= 0.00001655 \end{align}\)

Now repeat these calculations for every possible way of making up 30 friends from the known distribution. This can be done with an integer partition algorithm with a maximum on the values that each partition can take. For examples of such code, see the next post. All in all, there will be 16,632 different partitions for this particular set of maximums for 30 people. The sum will be the theoretical value of selecting friends who do not share birthdays. Subtract from 1 to get the probability of least 2 sharing a birthday.

In two equations:

\[\begin{align} p(x \geq 1 | D,n) &= 1 - \frac{1}{\binom{n}{N}}\sum_{p \in P(n, D)}\sum_{j=1}^{|p|} \binom{D_j}{p_j} \binom{j}{1}^{p_j} \\ N &= \sum_{j=1}^{|D|} D_j j \end{align}\]where $D$ is the distribution given as the frequency per shared count $j$, $n$ is the group size and $P(n, D)$ are the integer partitions of $n$ bounded by $D$.

For Julia code on my laptop this takes 22.5 seconds for all group sizes from 1 to 60 for a cumulative total of 1,099,174 partitions. Monte Carlo simulations with 10,000 trials per each point from 1 to 60 takes 2.2 seconds for all 600,000 trials. So the Monte Carlo simulations are faster.

If there is an easier way please let me know 🙂.