My take on the famous birthday problem.

intuitive [ɪnˈtjuːɪtɪv]

Using or based on what one feels to be true even without conscious reasoning; instinctive.

Definition from Oxford Languages

This is part of a short series on probability, a field rife with problems that are easy to understand but results that are decidedly not intuitive for people. This post is harder than last week’s on the Monty Hall problem. Some background in probability will help.

Introduction

If you’ve ever encountered two unrelated people who share a birthday, you might have wondered what the chances of it were happening. We can formalise this and ask how many people do you need to have a 50% chance of at least two people sharing a birthday? A 99% chance? A 100% chance? This is the famous birthday problem. Besides for being an amusing maths problem, it also has important consequences for hashing functions which are used in cryptography and key-value data stores.

The answers often surprise people. You need at least 366 people - more people than possible birthdays - to be dead certain that at least the 366th person shares a birthday with someone before him. But with just 57 people - 1/6th of 365 - you’re almost guaranteed to have a match. With only 23 people - 1/16th of 365 - you have a 50% chance of at least two people sharing a birthday.

In general, for $n$ unique items you need $\sqrt{n}$ instances for a 50% chance of collision, and $3\sqrt{n}$ for a 99% chance.

Why is the number of people required so low? The short answer is the large amount of combinations of pairs that can share birthdays. This number rises exponentially but most people apply a linear heuristic to this problem, which leads them to massively overestimate the answer.

Another important if obvious idea to keep in mind is that there is a much higher probability of any two people sharing a birthday than a specific person such as yourself sharing a birthday with someone else. (A related idea is that while there is a high chance of someone winning a lottery, there is a low chance of you winning it.)

Let’s investigate further.

Facebook friends

In high school, I was part of two classes of about 25 people each. In the first I shared a birthday with my twin brother, but also with someone else, and two others shared a birthday on another day. In the second, I only shared a birthday with my twin, which doesn’t count here because we are related. So in 50% of my classes, there was a 50% match.

You can also try this experiment in work departments and friendship circles. However, a more robust experiment is to use random samples of different sizes from connections on social media. I did this with 374 friends from Facebook.

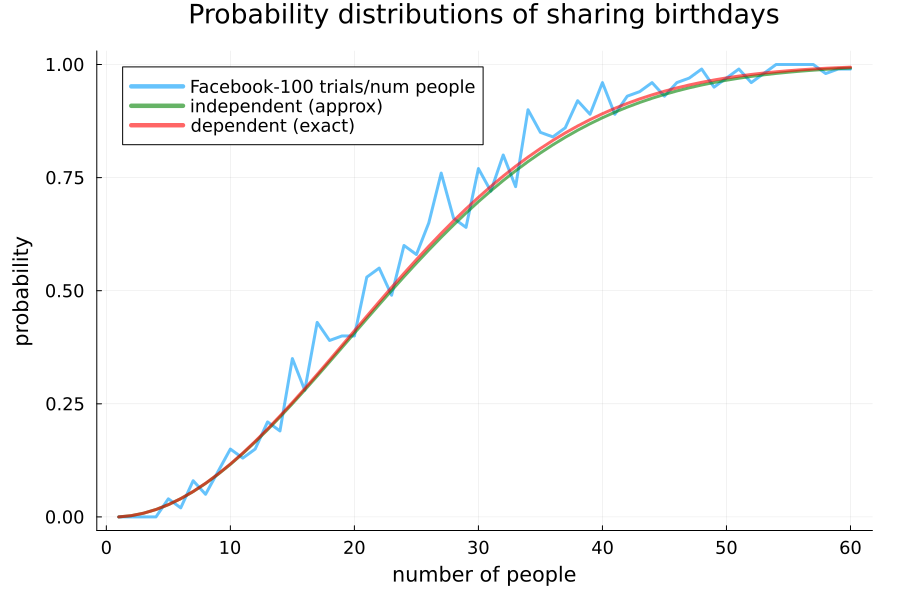

I ran a Monte Carlo simulation where I randomly picked different groups of these friends for each group size from 1 to 60 and recorded whether or not there was at least one shared birthday. I did this 100 times for each group size (6000 trials in total) and estimated the probability as the mean number of trials with shared birthdays. The blue graph above is the resulting curve. This is compared to an approximate formula for large populations (which will be explained below) and an exact formula (which is calculated in part 2).

Here is the pseudo code:

Monte Carlo simulation of birthday collisions

birthdays $\leftarrow$ list of birthdays of Facebook friends

probabilities $\leftarrow$ Array(60)

for group_size $\leftarrow 1:60$ do:

$\quad$ num_shared $\leftarrow 0$

$\quad$ for trial $\leftarrow 1:100$ do:

$\quad\quad$ group $\leftarrow$ rand_subset(birthdays, group_size)

$\quad\quad$ if has_collisions(group)

$\quad\quad\quad$ num_shared $\leftarrow$ num_shared $+ 1$

$\quad$ probabilities[group_size] $\leftarrow$ num_shared$/100$

return probabilities

See the appendix section for more details on the data.

The probability that you share a birthday with someone else

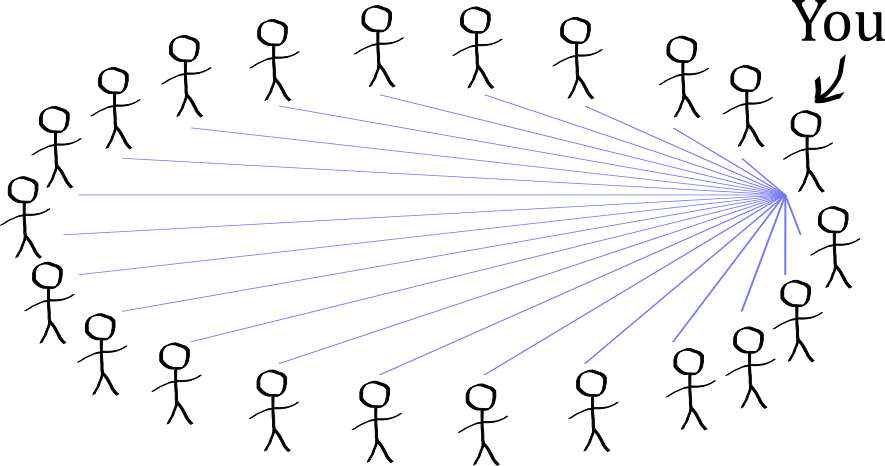

Let’s now calculate the theoretical probabilities. Imagine you are in a circle with 23 other people. What is the probability you share a birthday with someone else? This is specific to you. It does not matter if two other people share a birthday; it only matters if one other person shares a birthday with you.

To simplify calculations, it is easiest to assume that sharing a birthday with someone is independent of sharing it with anyone else. This is not entirely accurate. For example, if person A and person B share a birthday, then the probability of sharing a birthday with person B depends on the probability of sharing it with person A. In the highly unlikely case of everyone else having the same birthday, then the probability of sharing with anyone depends on everyone. But the assumption of independence is good because (1) most people will not share birthdays and (2) the events of multiple people sharing birthdays are very unlikely.

Under the assumption sharing is independent, you can imagine going to each and every person and asking them if they have the same birthday as you. There is a 1/365 chance they will say yes, and a 364/365 chance they will say no. For exactly one other person sharing a birthday with you, this is a standard binomial probability where there are 22 ways where 1 person will say yes and 21 will say no:

\[\begin{align} P(x=1) &= 22 \left(\frac{1}{365}\right)^1 \left(\frac{364}{365}\right)^{21} \\ &=0.0567 \end{align}\]But you could also share a birthday with two others, or three or four or everyone. These events are more unlikely than sharing with just one other person, but they will add to the total. Instead of calculating them all, it’s easier to work backwards and calculate the probability no-one shares a birthday with you and subtract it from 1. There is one way 22 people will say no:

\[\begin{align} P(x\geq 1) &= 1 - \left(\frac{364}{365}\right)^{22} \\ &=0.0586 \end{align}\]This is close to 23/365 which is about 6%. So far, the numbers are close to our expectations.

The probability that at least some people share a birthday

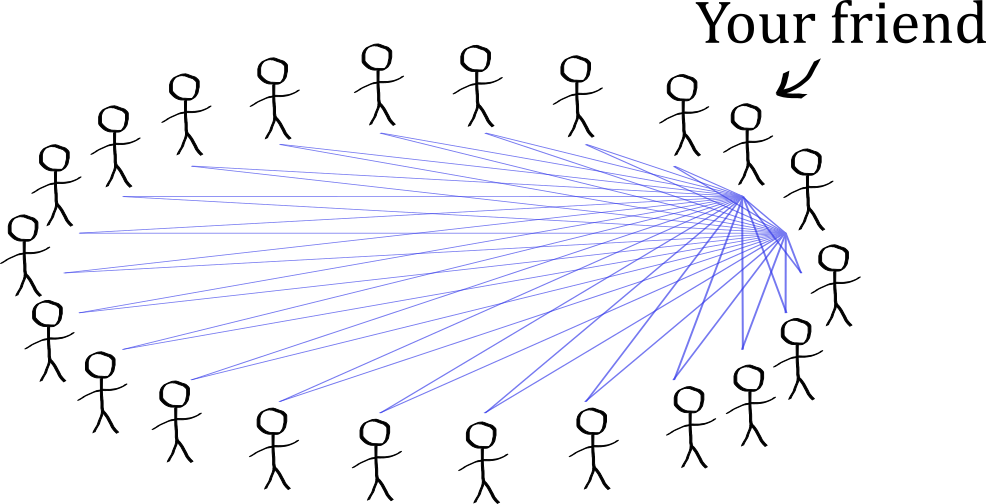

Your friend is sitting next to you in this circle. You now want to know the probability that either you or him share a birthday with someone. Intuitively this probability should be higher.

You have already asked 22 people, including your friend. So he now only needs to ask 21 people. Note that you have not compared your friend’s birthday with anyone else. Since you both “win” this game if one of you wins, losing is the equivalent of getting another 21 negatives, or $22+21=43$ negatives in total:

\[\begin{align} P(X\geq 1) &= 1 - \left(\frac{364}{365}\right)^{43} \\ &=0.1113 \end{align}\]Your friend does get all negatives. So you bring in a second friend. She only needs to ask 20 people if they share a birthday with her:

\[\begin{align} P(X\geq 1) &= 1 - \left(\frac{364}{365}\right)^{43+20} \\ &=0.1587 \end{align}\]You’ve more than doubled your original probability of 6% to 16%. Now let us go and compare with everyone else.

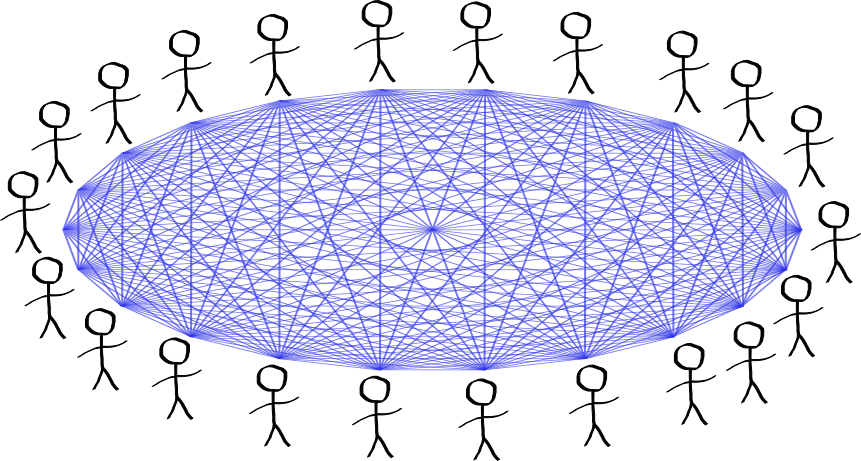

In total you will compare $22+21+…+2+1=253$ pairs of people. The final probability is:

\[\begin{align} P(X\geq 1) &= 1 - \left(\frac{364}{365}\right)^{253} \\ &=0.5005 \end{align}\]The fraction 253/365 is 69%, so it is an overestimate of the real probability of 50%.

Note that the chance of collision does not increase linearly. You could still compare 1000 pairs and fail.

In general, the number of pairs that can be formed is ${k \choose 2} = \frac{k(k-1)}{2}$. This is $k$ groups of $k-1$ pairs divided by 2 because you count every pair twice. So the number of combinations increases by $k^2$, which is why the number of people required for a collision with $n$ distinct items is proportional to $\sqrt{n}$.1

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed this article and now believe the chances, even if it still feels unintuitive. I suggest trying it out with your own Facebook friends or LinkedIn connections.

If you want more in-depth mathematics please see my next post on Advanced mathematics for the birthday problem.

Appendix: more details on my Facebook friends

I have over 400 Facebook friends. They are all real people. I have added them on Facebook over 14 years. They range from people I have only met once to my closest friends and family. Of these, 379 have publicly available birthdays. There are five sets of twins (myself included) which I count as one person, which leaves 374 birthdays.

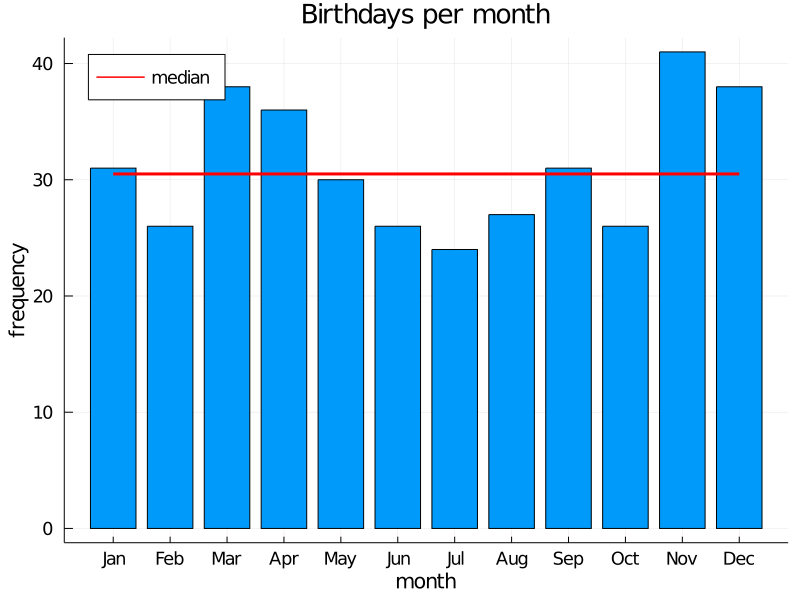

Here is the distribution of birthdays per month:

There are approximately 30 birthdays a month. Some months have more and some less. It can be considered a rough approximation of a uniform distribution of birthdays.

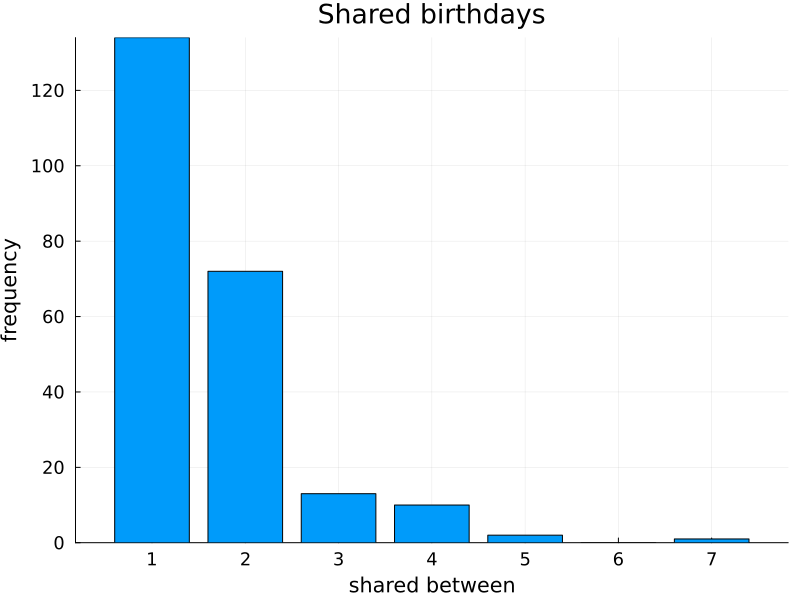

65% of my friends share a birthday with at least one other unrelated person. On one day there are as much as seven people sharing a birthday. This is the distribution of people with shared birthdays:

Because this is only a sample, the probabilities of sharing birthdays for my friends is slightly different to a large, theoretical population. For example, there is no chance of six of my friends sharing a birthday. However, this is only a slight difference overall. Part 2 calculates the theoretical probabilities for this given distribution of birthdays. That is, the probability of shared birthdays for an infinite number of Monte Carlo trials for groups of my Facebook friends.

-

Here is an approximation formula derivation:

\[\begin{align} 1-p &= \left(1-\frac{1}{n}\right)^{(k^2-k)/2} \\ \log(1-p) &= \frac{k^2-k}{2}\log\left(1-\frac{1}{n}\right) \\ \log(1-p) &\approx \frac{k^2-k}{2}\left(\frac{-1}{n}\right) \quad\quad, \log(1+x) \approx x \\ k^2 &\approx -2n\cdot \log(1-p) \quad\quad, k^2 >> k \\ k &= \sqrt{-2n\cdot \log(1-p)} \end{align}\]This is just an approximation, so no need to apply the quadratic formula for $k$. For $p=0.5$, $k=1.177\sqrt{n}$ and for $p=0.99$, $k=3.035\sqrt{n}$. Base of the logarithm is $e$. ↩